Abstract

The first bite of a fresh-picked apple, the crunch of morning toast, the deep cut into rich, flaky layers of baklava, the pleasing snap of a chip. Besides being delicious, what do these foods have in common? They're crisp. They have a brittleness that causes them to shatter in your mouth when you first bite into them. It's a sensation that many people enjoy. Making potatoes crispy requires some extra cooking steps, as you'll discover in this food science project, but the results are well worth the effort. If you love to cook, try this science fair project, and become, not a potato masher, but a potato master!Summary

Kristin Strong, Science Buddies

Objective

To determine if a cold-water soaking process can improve the crispness of oven-fried potatoes.

Introduction

Potatoes! These earthy, dimpled lumps are the most popular vegetable in the United States, and the biggest vegetable crop grown worldwide. Originally from Central and South America, potatoes were brought back to Europe by Spanish explorers in the 1500's where they were prized for being hardy and inexpensive. They were soon the main crop for entire populations of peasants. Around the time of the Irish potato disease in the middle of the 1800's, for example, people were eating 5-10 pounds of potatoes per person, per day!

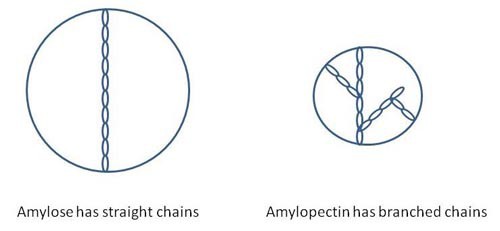

Potatoes are from the nightshade family of plants that includes peppers, tomatoes, and eggplant. Did you know that all these vegetables are related? Potatoes are a tuber, which is a swelling of starch and water that forms on the end of an underground stem. Plants grow tubers to store energy so that they can survive the winter and grow the next spring. The starch in the tuber is the stored energy. The starch molecules are long chains of thousands of simple-sugar molecules. There are two types of starch molecules: amylose and amylopectin. As shown in Figure 1, the amylose starch molecules have long, straight chains, while the amylopectin starch molecules are more compact and have branched chains. Potatoes and other tubers are unique in that their amylose chains are unusually long—four times longer than the starches in cereal grains. The granules that the starches are stored in are also much larger in potato tubers than the granules in most other vegetables and cereal grains. Tubers also contain a fraction of the lipids (fats) and proteins found in cereal starches. So, no matter what method you choose to cook your potatoes, the primary nutrient that you will be heating and transforming is starch.

Image Credit: Kristin Strong, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Kristin Strong, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 1. This drawing shows the two kinds of starch molecules.

Potatoes can be boiled, microwaved, or baked but by far the most popular way to cook them is by frying them, deep-frying them in a vat of oil. Potato chips and French fries are eaten all over the world, and the special trick of double-frying them to get them crisp, has been known as far back as the early 1800's when street vendors sold French fries (pommes frites) on the streets of Paris, France. If you take a potato, cut it into pieces, and simply fry it in oil, it will not develop a nice, crispy texture. Instead, only a thin, delicate crust will develop, and the water from the inside of the potato will quickly soften that crust, removing any crispness, and making it mushy. Two stages of frying are required for the crispness to last. First is a low-temperature frying, which allows the starch in the granules from the outermost layers of the potato pieces to leak out, dissolve, and form a glue, which strengthens the external wall of the potato pieces, so that a strong crust can form. This strong crust will not weaken from the moisture inside the potato when it undergoes the second stage of cooking, high-temperature frying. The high-temperature frying allows the surface browning reactions to take place, creating greater depth of flavor, and crispness.

So, if you don't have a deep-fat fryer and want to fry potatoes at home in an oven, is it possible to get this same level of crispness without the two-step frying method used to make commercial chips and French fries? Well, baking is a completely different process than frying in oil (deep-frying or otherwise). You know that baking is different because you can briefly put your hand into a hot oven (obviously not touching any surfaces!) without getting burned, but you cannot ever put your hand into hot oil without getting burned. In frying, the food is surrounded by oil, which is much denser than the air that surrounds food during baking. This high density causes the high-energy oil molecules to collide more frequently with the food than the high-energy air molecules do in baking. So, frying raises the temperature of the food much more quickly than baking does. In addition to the density issue, cold food in a warm oven develops a boundary layer around it, made up of both air molecules and water vapor evaporating from the food. This boundary layer slows down collisions of the warm air molecules with the food. Finally, the energy used in evaporating water from the food's surface reduces the energy around the food that is available to move to the center of the food, further slowing down the warming of the food. All of these factors taken together make baking a much less efficient cooking process than frying.

One way to improve the energy transfer from the hot oven air to a food like potatoes is to coat the potatoes in a thin layer of oil. This oil does not evaporate away the way the potato moisture will, and as the oil gains energy from the hot oven air molecules, it will transfer that energy to the potato, so that the potato surface will get hotter more quickly than it would without the oil. The oil also adds to surface browning reactions to give more richness and crispness to the potatoes. Another way crispness is improved is by rinsing the excess starch from the potatoes by soaking them in cold water before coating them in oil and baking them. If the extra starch is left on, it blocks the evaporation of moisture from the potato and the result is a softer, mushier fried potato.

What kind of potato is best for frying? Well, with over 200 species of potatoes to choose from, it may seem hard to answer that question, but all these potatoes can be divided into two broad categories: mealy and waxy, based on how much starch is concentrated in their granules. Potatoes that concentrate the most starch are denser and are known as mealy potatoes. Examples are russets, Russian fingerlings, banana fingerlings, and purple varieties. When these potatoes are cooked, their cells tend to swell and separate, creating potatoes that are fluffy and dry. These varieties work well for frying, baking, and mashed potatoes. Potatoes that concentrate less starch are known as waxy potatoes (you may have heard them also described as boiling potatoes). Examples are red and white-skinned potatoes, and new potatoes. When these potatoes are cooked, their cells do not separate, so the resulting potato has a smooth, moist texture that works well in potato salads, stews, and gratins.

So now that you're a potato master (that's master, not masher), you're ready to put these ideas to the test, and see if you can get your oven to make the perfect, crispy, oven-fried potato.

Terms and Concepts

- Nightshade family

- Tuber

- Starch

- Simple sugar

- Amylose

- Amylopectin

- Granule

- Lipid

- Protein

- Boil

- Microwave

- Bake

- Fry

- Double-fry

- Surface browning reaction

- Density

- Boundary layer

- Evaporation

- Efficiency

- Energy transfer

- Mealy

- Waxy

- Solanine

Questions

- Where in the world are potatoes from and why are they so popular?

- To what other vegetables are potatoes related?

- What is the main food nutrient within potatoes?

- Why do deep-fried potatoes need a two-stage frying process?

- How is baking different from frying?

Bibliography

- McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking. New York, NY: Scribner, 2004.

- Brown, A. (2007). Fry Hard Transcript. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

Materials and Equipment

Caution: Never eat any potato that is bitter, or that has a green color just below the skin, as this can indicate that the potato has built up dangerous levels of solanine, a substance that the potato produces as protection against insects, other animals, and disease.

- Baking potatoes (3)

- Vegetable brush

- Vegetable peeler (optional)

- Cutting board

- Knife

- Large bowl

- Medium bowl or pan

- Cold water

- Paper towels (8 sheets) or clean dishcloths (2)

- Olive oil, 2 tablespoons (tbsp.)

- Salt, 1 teaspoon (tsp.)

- Tablespoon

- Teaspoon

- Baking sheet or shallow roasting pan

- Spatula

- Cooling rack

- Oven mitts

- Lab notebook

Experimental Procedure

Preparing Your Potatoes for Testing

- Rinse the potatoes and scrub away any excess dirt with the vegetable brush.

- Peel the potatoes, if desired, or leave the skins on.

-

Cut the potatoes into sixteenths. Be sure to have an adult help you use the knife.

- Cut each potato lengthwise.

- Cut each half lengthwise.

- Cut each quarter into four wedges, so that your entire potato is cut into 16 pieces. If you prefer thinner wedges, you can cut the wedges one more time, so that the entire potato is cut into 32, rather than 16, pieces. See Figure 2, below.

- Separate the potato wedges into two equal piles. Leave one pile alone. In the other pile, use your knife to cut a small, triangular notch on the side, near the end of each wedge (on the non-skin side). See Figure 4, below, for examples.

- Place the pile of potatoes with notches on a clean dishcloth or layered stack of paper towels for a few minutes to help air-dry them, and then put them into the large bowl.

- Submerge the pile of potatoes without notches into a medium bowl of cold water, as shown below. Run cold water over the bowl for approximately 1 minute, so that it overflows. Then turn off the water, and let the potatoes sit submerged in the cold water for at least 20 minutes. This will help eliminate any excess starch.

Image Credit: Kristin Strong, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Kristin Strong, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 2. These photos show how to rinse and soak the potatoes without notches.

- After the 20 minutes, pour the submerged potatoes into a strainer and let them drain for approximately 5 minutes.

- Place the pile of potatoes without notches on a clean dishcloth or layered stack of paper towels for a few minutes to help dry them.

- Preheat the oven to 450°F.

- Add the potatoes without notches to the large bowl with the potatoes with notches.

- Add 2 tbsp. of olive oil and 1 tsp. of salt to the large bowl with all the potatoes inside. With clean hands or two large spoons, toss the potatoes with the olive oil and salt until the potatoes are completely and evenly coated with oil and salt.

Image Credit: Kristin Strong, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Kristin Strong, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 3. This photo shows the potato wedges after being dried and coated evenly with oil and salt.

Oven-frying Your Potatoes

- Spread all the potatoes out evenly (in a single layer) on a baking sheet or shallow roasting pan.

Image Credit: Kristin Strong, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Kristin Strong, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 4. This photo shows all the potato wedges spread out evenly in a single layer. You can see that some of the potatoes have triangular notches and some do not.

- Bake the potatoes at 450°F for 10 minutes. Have an adult use the oven mitts to remove the roasting pan or baking sheet from the oven and gently turn the potatoes over with a spatula.

- Return the potatoes to the oven and bake for 10 more minutes. Have an adult use the oven mitts to remove the roasting pan or baking sheet from the oven and gently turn the potatoes over with a spatula.

- Return the potatoes to the oven and bake an additional 10 minutes, or until golden brown.

- Transfer the potatoes to a cooling rack and allow them to cool down.

- Select three potato wedges without notches, and three potatoes with notches. Examine their color and write down your observations in your lab notebook.

- Place a potato wedge on the edge of a table and gently hold it down with one hand so that one-third of it is resting on the table and the other two-thirds are hanging off the table.

- With your other hand, press down on the end of the potato wedge hanging off the table.

- If the potato wedge snaps into two pieces, write down "crispy" in a data table in your lab notebook, like the one below. If the wedge just bends under pressure, and doesn't break, write down "soft" in your data table.

- Repeat steps 7–9 for the remaining five potato wedges.

Analyzing Your Data

- Examine your data table. Which potato preparation process produced more wedges that were crispy than soft?

Potato Crispness Data Table

| Potato Preparation Process Before Baking in Oil and Salt | Potato Wedge 1 | Potato Wedge 2 | Potato Wedge 3 | More Crispy Wedges or More Soft Wedges? |

| Not Soaked in Cold Water (Notched Potato) | ||||

| Soaked in Cold Water (No Notches) |

- Sprinkle your extra (untested) potatoes with salt and serve!

Ask an Expert

Variations

- Add a taste test to the experiment to see if your volunteers prefer the texture and taste of the cold-water soak method over the no-soak method.

- Prepare the potatoes as described above, but skip the cold-water soak. Test if a long, low-temperature oven-fry, followed by a short, high-temperature oven-fry does a good job of crisping potatoes. Which does a better job? A double oven-fry or a cold-water soak?

Careers

If you like this project, you might enjoy exploring these related careers: