Abstract

Have you ever wondered how virtual reality works? With virtual reality, people feel like they are in one place while knowing they are somewhere else. In this project, you will show the same phenomenon on a smaller scale. You will use the McGurk effect to show how you can hear one sound, while knowing a different sound is physically there. First, you will produce such an experience using audio and video, and then measure the strength of the phenomenon.Summary

This project requires the participation of volunteers. Make sure you are familiar with your science fair's rules about tests involving human volunteers before you start. For suggestions and common rules check out the Science Buddies resource Projects Involving Human Subjects.

- Windows is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corporation.

Objective

Create a video showing the McGurk effect, where your volunteers will hear a sound differently from what is physically there, then change the timing of the audio track to measure the strength of the phenomenon.

Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) is an exciting area, and not only in the gaming and entertainment world. It is already proving its benefits in areas where people need to learn a skill without risking the dangers involved in the real experience. The Bibliography can help you investigate areas where VR can be useful, as well as identify potential dangers of VR.

Virtual reality creates the illusion that people are in one place (the virtual environment), while knowing they are somewhere else. Curious about how it works? To understand VR, it is important to know that experiences are created in the brain as it integrates all the information received from all our senses. In most cases, the information received is coherent and the experience matches what is really there. In some cases, the information is dubious or contradicting, and our brain creates the best match. This can create illusions, or false impressions. Some illusions are so strong that even when we know the interpretation is wrong, we cannot help but experience it this way. Virtual reality controls what we see, hear, feel, or maybe even smell to create desired illusions. It uses these to make us feel we are in one place doing one thing, while we know we are in a different place doing something different.

The McGurk effect is a way to show this type of illusion (the illusion that results from manipulating our sensory input) on a smaller scale. The illusion results from conflicting visual and auditory information reaching our brain. It can happen when the mouth movements you see when someone talks contradict with the sound reaching your ears. What do you think you will experience in this case: the sound corresponding to the lip movements, the sound reaching your ear, or a third sound? Watch the video below and experience the McGurk effect for yourself.

The McGurk effect is a great demonstration of how, like in VR, you can know that something is not real; at the same time, you cannot stop yourself from experiencing it. It demonstrates that by controlling the information that is received by our senses, we can control our perception of the environment.

Ready to try it out yourself? In this project, you will create your own video illustrating the McGurk effect. You will then shift the audio track in time, with respect to the video track. Will the McGurk effect still work if the auditory and visual stimuli are not simultaneous? Get ready to find out!

Terms and Concepts

- Virtual reality

- Experience

- Coherent

- Illusion

- McGurk effect

- Stimulus

Questions

- What is your understanding of what happens in the brain when the McGurk effect takes place?

- The McGurk effect persists in subjects expecting the effect. Even when the subject knows he or she is being tested with the effect, he or she still hears sounds that are different from the sound that is really there. How is this similar to what happens in virtual reality experiences?

- Do some background research on the McGurk effect. Does it happen for all sound combinations or only for particular combinations? Do people always hear the sound that is related to the visual stimulus or can a sound that is different from the visual and the auditory stimuli be perceived?

Bibliography

The following reference will provide information about the McGurk effect.- McCulloch, G. (2014, June 27). When Your Eyes Hear Better Than Your Ears: The McGurk Effect. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- Sackman, D. (2015, February 20). Real change through virtual reality. TEDxEastEnd. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- Kim, M. (2015, February 18). The Good and the Bad of Escaping to Virtual Reality. The Atlantic. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- Microsoft® (n.d.). Windows Essentials: Movie Maker. http://windows.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-live/windows-essentials-help#v1h=tab1

Materials and Equipment

- Ability to take a video; some options are:

- Video camera

- Cell phone with video capacity

- Tablet or computer with a camera

- Computer with video processing software. See the Procedure for more details.

- A "test panel" of 8–10 volunteers

- Highlighters (3 different colors)

- Lab notebook

Experimental Procedure

Working with Human Test Subjects

There are special considerations when designing an experiment involving human subjects. Fairs affiliated with Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) often require an Informed Consent Form (permission sheet) for every participant who is questioned. Consult the rules and regulations of the science fair that you are entering, prior to performing experiments or surveys. Please refer to the Science Buddies documents Projects Involving Human Subjects and Scientific Review Committee for additional important requirements. If you are working with minors, you must get advance permission from the children's parents or guardians (and teachers if you are performing the test while they are in school) to make sure that it is all right for the children to participate in the science fair project. Here are suggested guidelines for obtaining permission for working with minors:

- Write a clear description of your science fair project, what you are studying, and what you hope to learn. Include how the child will be tested. Include a paragraph where you get a parent's or guardian's and/or teacher's signature.

- Print out as many copies as you need for each child you will be surveying.

- Pass out the permission sheet to the children or to the teachers of the children to give to the parents. You must have permission for all the children in order to be able to use them as test subjects.

This project requires you to take a video and use video editing tools. Here are some options to take a video:

- Video camera

- Cell phone with video capacity

- Tablet or computer with a camera

Here are some options for Video editing:

- If you have Windows® as operating system on your computer, you might have Windows Movie Maker on your computer, or you can download it from Microsoft Movie Maker. The Bibliography includes a link to help you learn how to use Windows Movie Maker.

- If you are using a different computer operating system, an internet search for "Free Video Editing Software for..." (where you fill in your operating system) might give you some options.

- You could also ask your friends if they are familiar with video editing tools and can help you with your science project.

Creating the Videos

As mentioned in the Introduction, you will create your own video illustrating the McGurk effect. You will then create multiple versions of this video. For each version, you will shift the audio track in time, with respect to the video track. You will use the videos in a survey to measure by how much you can delay the auditory stimulus with respect to the visual stimulus and still get the McGurk effect for most of your volunteers. In this step, you will create the videos you will use in your survey.

- If you are not familiar with the McGurk effect, look at the video provided in the Introduction before you start.

- Do some background research on the McGurk effect and choose a sound combination you would like to test. Table 1 lists some examples.

| Visual Stimulus | Auditory stimulus | Perceived sound when looking at the video |

|---|---|---|

| Can | Cap | Cat |

| Gate | Bait | Date |

| Aba | Apa | Aka |

| Gaga | Baba | Gaga |

| Aka | Apa | Aka |

- Take the video of a person repeating the visual stimulus. You can use your favorite way of making videos, or try one of the following options:

- A cell phone's or a photo camera's video recording options

- A video camera

- A camera installed in a laptop or tablet

Windows Movie Maker is just one program that allows you to make a video with the camera on your computer.

Show the face, especially the mouth, clearly in your video. Have the person repeat the stimulus three times. A repeated stimulus can confirm the effect more clearly.

- Edit your video. Remember to check the "Help" files of your video editing software if you have difficulty with any of these steps. A link to the help files of Windows Movie Maker is included in the Bibliography.

- Open the video editing software of your choice and load the video, or take the video with the software.

- Trim any unwanted parts.

- Save this video as "original".

- Remove the sound. As you will see in the next two steps, setting the volume to zero is preferred over removing the soundtrack completely. Keeping the silenced original audio track makes synchronization easier.

- Record a new soundtrack for your video with the chosen auditory stimulus. Do your best to synchronize the recorded audio with the movements of the lips. Note that most video editing tools allow you to record a new soundtrack.

- Fine-tune the start point of the audio soundtrack so the visual stimulus (seeing the lip movements) is simultaneous with the auditory stimulus (hearing the sound). This can be tricky. The following tips will help:

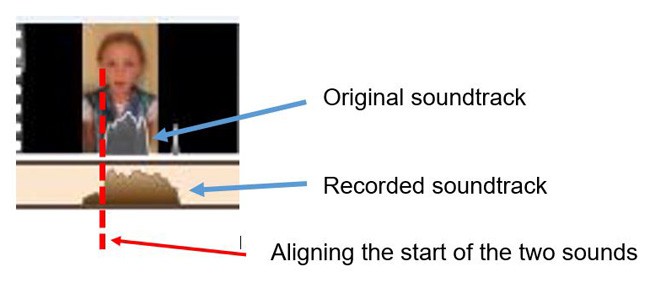

- See if your video editing tool can show the volume distribution over time of the original audio track, and the recorded audio track, one below the other, as shown in Figure 1. This will allow you to visually evaluate synchronicity.

- Video editing tools often allow you to split and shift recorded audio. Look for "Editing - Narration tools" or "Editing - Audio track" of your particular video editing tool to find help.

Image Credit: Sabine De Brabandere, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Sabine De Brabandere, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 1. This figure shows how, in Movie Maker, you can see the volume distribution of the original soundtrack (grey) together with the recorded soundtrack (brown). In this case, the original sound was shorter in time than the dubbed sound. Notice how the sudden increase in volume for both sounds are aligned in this picture.

- Evaluate your video. Do you get a McGurk effect when watching your video?

Go to the next step if you are satisfied; rework your video if you feel it needs improvement. Here are some hints that might help you identify ways to improve:

- Is the mouth clearly visible in the video?

- Are the lips moving clearly? There is no need to overdo articulation and make it seem unnatural. Normal speech from a person who articulates well is optimal.

- Are there too many other distractors in the video or on the audio track?

- Is the synchronization well done? Does the auditory stimulus coincide with the visual stimulus?

- Are the sound choices working well? Maybe choose a different visual and auditory stimulus and see if that works better.

Depending on your findings, you might want to retake the video or re-edit the video. Do not give up! It might take a couple of rounds before you get it right, especially if you are new to video editing.

- Save your work as a project in the native file format for your video editing program and as a video (MP4 or other common filetype). Look up 'publish', 'Make Movie' or 'Export' in the help function of your video editing tool if you need instructions on how to do this. Note that the project file will allow you to re-edit and change your video. The MP4 file on the other hand is smaller and can easily be shared with others, but does not contain as much of the original information. Choose a name that will inform you later what is in the video; for example, the name might be " VCan-ACap-Original", indicating that the visual stimulus "Can" was combined with the auditory stimulus "Cap" in this video.

- Create videos with delayed audio track.

- Load your project in your chosen video editing software and rename the project by switching "Original" to "Delayed 100 ms" in the project name. This way, you will not accidentally overwrite your original project.

- Shift the recorded audio track by 100 milliseconds (ms) backward so the visual stimulus precedes the auditory stimulus by 100 ms delay. If you have trouble finding how to do this, look up "Shift start point audio track" in the help function of your video editing tool; this might provide the information you are looking for.

- Save the new video as video and as a project.

- Repeat steps a–c for 200 ms and 400 ms.

- Evaluate your videos with a time delay included. Is the McGurk effect strong on all your videos, or only on some? Will this set of videos be able to confirm or rule out your hypothesis, or would a different set of time delays work better in your case?

Collecting Data

- In this section, you will investigate how other people perceive your video. Start by creating a table in your lab notebook, like Table 2, in which to collect all your data.

| Visual stimulus: ..... Auditory stimulus: ..... | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of test | Volunteer identification | Perceived sound - no delay | Perceived sound - 100 ms delay | Perceived sound - 200 ms delay | Perceived sound - 400 ms delay | Perceived sound - Looking away (or closing eyes) |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | ||||||

| ... | ||||||

- Next, recruit your volunteers for the test. Your volunteers should not be blind or hard of hearing. 8–10 people is a good number, but if you find more, that is even better. The Science Buddies resource Sample Size: How Many Survey Participants Do I Need? shows the relationship between the number of participants and the accuracy of your findings.

- For this experiment, it is okay to show the videos to multiple volunteers at the same time, as long as you take the following precautions:

- Make sure all the volunteers can see the video well.

- Be sure that all volunteers write their answers down and do not communicate their answers to other volunteers while you do the test. Volunteers should not influence each other.

- Assign each volunteer an identification number so that your data can be recorded anonymously.

- Perform the tests:

- Explain to the volunteer(s) that you would like them to look at, and listen to, four videos and that for each video they should write down the sounds they perceive. Let them know that for one more video, you will ask them to only listen, not look at the video, and they should again write down the sounds they perceive.

- Explain that if they perceive the same sound repeatedly, they only need to write down that one sound for this video, but if they perceive different sounds in one video, ask them to write down all three perceived sounds for that video.

- Randomly choose the order in which you will show the videos and perform the test. Remember to write down the order in which you will play the videos, so you can match the volunteers' answers to the video played.

- After showing the four videos, ask the volunteer(s) to close their eyes or not look at the screen. Then, let the volunteer(s) listen to the first video and ask them to note down what they perceive.

- Collect the answers and thank your volunteers.

- If the volunteers are interested, explain to them the McGurk effect you are studying and ask if they would like to see your videos again. You might like to show them your original video (without dubbing) as well.

- Add your data to the data table.

- If people perceived different sounds in one video, write down all three answers.

Analyzing the Data

- Colors can help identify patterns in your data. For that reason, use highlighters to identify different categories, as described below:

- Highlight all the cells in your data table where the perceived sound is identical to the auditory stimulus for all three stimuli in one color (such as yellow).

- Repeat step a. with different colors (such as blue and green) for perceived sound being identical to the visual stimulus and for perceived sound being identical to a third, different sound.

- The leftover cells all have responses that fall in more than one category. Use the color corresponding to the category that best fits the responses to lightly color in those cells.

- Summarize your data in numbers by counting, for each video, how many volunteers perceived the auditory stimulus, visual stimulus, or a third sound.

- Start with the auditory stimulus. Count the number of cells highlighted in a bright color corresponding to perceiving the auditory stimulus for all three stimuli (such as all yellow highlighted cells). Do not take into account the lightly colored cells from step 1.c. yet.

- Now, go over all lightly colored cells and add 1/3 for each answer where the volunteer perceived the auditory stimulus. (Note that the lightly colored cells all have three answers.)

- Write down the total in the table like Table 3 in the matching cell.

- Repeat your counting algorithm (steps a–c) for the two other categories (perceived sound being identical to the visual stimulus and perceived sound being identical to a third, different sound).

| Visual stimulus: ..... Auditory stimulus: ..... Number of participants: ..... | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No delay | 100 ms delay | 200 ms delay | 400 ms delay | Control: Looking away | |

| Perceiving auditory stimulus | |||||

| Perceiving visual stimulus | |||||

| Perceiving a third sound | |||||

- Create a bar graph for each category (auditory stimulus perceived, visual stimulus perceived, and a third sound perceived), with the delay time and the control (looking away) on the horizontal axis and the number of occurrences for that category on the vertical axis. Advanced students can combine these three bar graphs into one graph using different colors.

- Looking at your data and your graph(s), how sensitive would you say the McGurk effect is to audio-video time delay in your test case?

- Do you think your results reveal something about how strong or weak the McGurk effect is?

- Having studied the McGurk effect, would you say it might be possible to repeatedly create an experience different from the one we know is there, something VR claims to do?

Ask an Expert

Global Connections

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) are a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all.

Variations

- In this project, you study how a delay between the visual and auditory stimuli affect the McGurk effect experience. Can you find other parameters that might influence the effect? Some suggestions are the presence of background noise, inferior video quality, or the presence of other auditory or visual distractors.

- In this project, you did not explain the McGurk effect to your volunteers before you performed the test. You could repeat the experiment with the same volunteers and see if the results change after the volunteers learned how the McGurk effect works and know the sound that is really there.

- In this project, you studied the effect of a time delay for one particular stimulus combination. You can pick a different set of stimulus combinations (see Table 1) and study if some are stronger than others, measured by the time delay for which the effect no longer works.

- Ideally, a VR experience should be universal. Could you test if the McGurk effect is universal? Would different native language speakers experience the effect in the same way?

- Do some research on the visual information that is important for speech recognition. Examples are: would side vision work? Would the left side of the mouth be more important than the right? Then, investigate it you see the same difference in the McGurk effect. For example, if the left side of the mouth is more important than the right for speech recognition, would the McGurk effect work better if you show only the left side of the mouth with respect to when you show only the right side?

- Would the McGurk effect also work when you see a side view of the person speaking?

Careers

If you like this project, you might enjoy exploring these related careers:

Related Links

- Science Fair Project Guide

- Other Ideas Like This

- Human Behavior Project Ideas

- Virtual Reality Project Ideas

- My Favorites