Abstract

In this biology science fair project, you will observe how the Physarum polycephalum (P. polycephalum) organism responds to various amounts of glucose. P. polycephalum is easy to grow in a petri dish and responds in complex ways to its environment. Will it grow toward the chemical as it looks for a meal, or will it flee, trying to avoid further contact? Try this science fair project to learn more about chemotaxis in the fascinating Physarum polycephalum.Summary

David B. Whyte, PhD, Science Buddies

The procedure is modified from Bozzone, D. M. 2005. Using microbial eukaryotes for laboratory instruction and student inquiry. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

Objective

Explore chemotactic responses of P. polycephalum in culture exposed to various amounts of glucose.

Introduction

If you have walked through a wooded area that's still damp from a recent rain, you may well have seen a Physarum growing on a tree stump or among the fallen leaves. Members of the genus Physarum are also called slime molds. Slime molds are classified with protists. More than 700 different species of slime molds exist. They have a two-part life cycle. During warm, moist weather, a slime mold lives as a shapeless, growing blob called a plasmodium. The plasmodium may be gray, cream, colorless, bright yellow, or orange. A plasmodium slowly creeps across the ground, moving like an amoeba and consuming bacteria, fungi, and organic debris as it moves. When the environment dries out, the plasmodium transforms into many small, often stalk-like, fruiting bodies that are full of dust-like spores. The tiny spores can remain dormant in the soil for years, waiting for wet weather, at which time they release small, motile (capable of movement) cells. Two motile cells fuse together and grow to become a new plasmodium, starting a new cycle of life.

In order to survive, a Physarum plasmodium searching for food has to respond appropriately to environmental cues. It is constantly "deciding" which way to move: toward areas that will have food or away from areas that contain harmful substances. Part of the "input data" the plasmodium relies on to make this kind decision is based on chemical cues. If the organism senses chemicals that indicate the presence of food, it will move toward the area with more of that chemical. If it senses chemicals that are harmful, it will move to avoid further contact. Movement in response to a chemical signal is called chemotaxis.

Because chemotaxis is easy to observe and measure in Physarum, you can investigate various factors that affect it. In this biology science fair project, you will determine how the chemotactic responses of a Physarum polycephalum (P. polycephalum) plasmodium growing in culture depends on the concentration of glucose.

Terms and Concepts

- Physarum

- Slime mold

- Protist

- Plasmodium

- Fruiting body

- Environmental cue

- Chemical cue

- Chemotaxis

- Physarum polycephalum

- Millimolar concentration

Questions

- To what other environmental cues do you think a moving plasmodium might respond?

- How many species of Physarum are found in the state in which you live?

- Based on your research, what are the various stages in the Physarum's life cycle?

- If you go to the kitchen when you smell something cooking, is that an example of chemotaxis?

Bibliography

- Bozzone, D. M. (2005). Using Microbial Eukaryotes for Laboratory Instruction and Student Inquiry. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

Materials and Equipment

These items can be purchased from Carolina Biological Supply Company, a Science Buddies Approved Supplier:

- Chemotaxis in Physarum polycephalum Kit. The kit contains the following:

- Physarum culture, as plasmodium on agar plate

- Petri dishes

- Non-nutrient agar

- Oatmeal flakes (Physarum "food")

- Filter paper

- Aluminum foil

- Beaker, 250 mL

- Graduated cylinder, 10 mL

- Graduated cylinder, 100 mL

- Disposable gloves. Alternatively, these can be purchased at a local drug store or pharmacy. If you are allergic to latex, use vinyl or polyethylene gloves.

You will also need to gather these items:

- Microwave

- Oven mitt

- Plastic knives (1 box)

- Ruler, metric

- Plastic cups (12)

- Permanent marker

- Distilled water (1 gallon)

- Glucose tablets, 4 g/tablet; available at most drug stores or online at Amazon.com.

- Scissors

- Forceps or tweezers

- Lab notebook

- Optional: Digital camera

- Graph paper

Disclaimer: Science Buddies participates in affiliate programs with Home Science Tools, Amazon.com, Carolina Biological, and Jameco Electronics. Proceeds from the affiliate programs help support Science Buddies, a 501(c)(3) public charity, and keep our resources free for everyone. Our top priority is student learning. If you have any comments (positive or negative) related to purchases you've made for science projects from recommendations on our site, please let us know. Write to us at scibuddy@sciencebuddies.org.

Experimental Procedure

For health and safety reasons, science fairs regulate what kinds of biological materials can be used in science fair projects. You should check with your science fair's Scientific Review Committee before starting this experiment to make sure your science fair project complies with all local rules. Many science fairs follow Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) regulations. For more information, visit these Science Buddies pages: Project Involving Potentially Hazardous Biological Agents and Scientific Review Committee. You can also visit the webpage ISEF Rules & Guidelines directly.

Important Notes Before You Begin:

- Be sure you thoroughly read the procedure before beginning so you know how much time each step will take and can plan your schedule accordingly.

- Follow the steps below to make culture plates of Physarum for your experiments. The cultures will be grown on agar, and then transferred to fresh agar plates when the Physarum covers the old plate. The goal is to establish a healthy stock of growing plasmodia for your experiments.

- Loosen the top of a bottle of non-nutrient agar.

- Heat the non-nutrient agar in a microwave until it is liquid. Use an oven mitt to remove it if the bottle is hot.

- Pour the agar into 10 petri dishes so that the bottoms are covered.

-

Let the agar harden.

- For long-term storage, wrap the petri dishes in their plastic sleeves and store them in a refrigerator until you are ready to use them.

- Put on your disposable gloves. Count out 25 sterile oatmeal flakes for each agar surface and place them on top of the agar.

-

Cut out a piece of agar with plasmodium attached from the Physarum polycephalum culture that came with the kit. Read the following before you begin:

- Use a plastic knife.

- The piece should be about 1 cm by 1 cm.

- Place the agar block, with the plasmodium facing down, on one of the agar plates (which are the petri dishes now containing agar) that you made in steps 3–5.

- Place a lid on the plate.

- Wrap the plate in aluminum foil.

-

Monitor the culture daily, until you see enough growth. Use your judgment.

- To keep the culture healthy, transfer the culture to fresh plates (the additional ones you made in steps 3–5) every 3–4 days. To transfer to fresh plates, follow steps 6–8 of this section, except cut out a piece from your culture, not from the kit.

- To dispose of older cultures, wrap them in aluminum foil and place them in your regular garbage.

- Begin your experiments once you have established a stock of growing Physarum cultures.

Making Solutions with Varying Concentrations of Glucose

- Label five plastic cups: 100, 10, 1.0, 0.10, and Blank.

- Place a glucose tablet in the cup labeled 100 and add 222 mL of water using the 250-mL beaker.

-

Let the tablet of glucose dissolve completely.

-

This is a 100-mM solution.

- mM stands for millimolar. It is a way of measuring the concentration of an ingredient in solution. For more information about molarity, see the reference by Uri Lachish in the Bibliography in the Background.

- The solution may be slightly hazy due to additives in the tablet. You can ignore this.

-

This is a 100-mM solution.

-

Make a 10-mM solution:

- Use the cup labeled 10.

- Mix 10 mL of the 100-mM solution with 90 mL of distilled water.

- Use the 10-mL graduated cylinder and the 100-mL graduated cylinder to measure volumes.

- Mix the solutions in a clean plastic cup.

- Thoroughly wash the graduated cylinders between uses.

-

Make a 1-mM solution.

- Use the cup labeled 1.

- Mix 10 mL of the 10-mM solution with 90 mL of distilled water.

- Use the 10-mL graduated cylinder and the 100-mL graduated cylinder to measure volumes.

- Mix the solutions in a clean plastic cup.

- Thoroughly wash the graduated cylinders.

-

Make a 0.1-mM solution.

-

Use the cup labeled 0.1.

- Mix 10 mL of the 1.0-mM solution with 90 mL of distilled water.

- Use the 10-mL graduated cylinder and the 100-mL graduated cylinder to measure volumes.

- Mix the solutions in a clean plastic cup.

-

Use the cup labeled 0.1.

- Pour 200 mL of distilled water into the cup labeled Blank.

Preparing Plates with Paper Strips

- Label five clean petri dishes (without agar), as follows: 100, 10, 1.0, 0.10, and Blank.

- Cut filter paper into 10 strips, each approximately 8 cm x 2 cm.

- Soak six filter paper strips in the distilled water, the Blank cup.

- Using a permanent marker, label four dry strips 100, 10, 1.0, and 0.10.

- Soak the labeled strips of filter paper in the appropriate cups containing glucose: 100 mM, 10 mM, 1.0 mM, or 0.10 mM.

- Allow the filter paper strips to soak for at least 15 min.

- Using forceps, take a filter paper strip from the distilled water, the cup labeled Blank. Allow excess fluid to drip off.

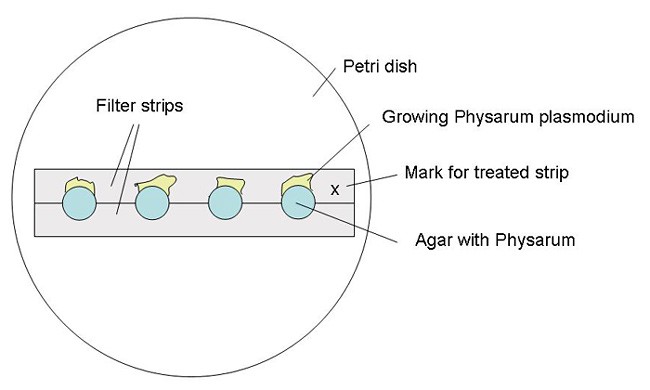

- Place five of the wet strips from the Blank cup on the bottom of each of the five sterile petri dishes, near the middle. See Figure 1.

Image Credit: David Whyte, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: David Whyte, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 1. Experimental setup to test Physarum polycephalum chemotaxis using the filter paper strip method. Two strips of filter paper are placed below a growing Physarum culture. One strip was dipped in a test solution (marked with an "x") and the other strip was dipped in distilled water, the cup labeled Blank. In this example, all of the tests are "positive" for growth toward the strip with the test substance.

- Place the last wet strip from the Blank solution next to the strip in the plate labeled Blank.

- The two strips should abut against one another. See Figure 1.

- Remove a filter paper strip from the 100-mM glucose beaker; allow excess fluid to drip, and place the strip right next to the distilled water strip on the bottom of the petri dish labeled 100. The two strips should abut against one another.

- Repeat for the strips and plates marked 10, 1.0, and 0.10.

-

Use a clean plastic knife to cut a plasmodium culture into blocks sized 0.5 cm x 0.5 cm.

- The plates you made with growing Physarum are plasmodium cultures. Now you can cut them up and use them for your experiments.

- Cut as many blocks as you need.

-

Transfer four such blocks, plasmodium-side down, onto the junction of the two filter paper strips. See Figure 1 for an idea of spacing.

- When you select the agar block with Physarum to transfer, be sure that you cut a thick vein or sheet of "tissue" located toward the edge of the plasmodium. Do not transfer pieces of oatmeal from the stock culture.

- Repeat for all of the filter strip petri dishes.

- Wrap the dishes in aluminum foil and incubate them right side up at room temperature.

- Observe plasmodium movement every hour for several hours, and again the next day. You will need to unwrap the plates to observe them, but be sure you wrap them back up again. The yellow plasmodia will be easily seen if they migrate onto the white filter paper.

Observing the Plates

-

Record all observations in your lab notebook, as follows. As an option, you could take pictures with a digital camera for your Science Project Display Board.

- For each plate, record the number of cultures that are growing farther into the glucose as Positive Toward Glucose in your lab notebook.

- Record the number of cultures that are growing equally in the glucose or the water strips as Neutral.

- Record the number of cultures that are growing farther toward the Blank strip as Negative, Away from Glucose.

- Use your judgment about what to score as positive, neutral, or negative.

Repeating the Procedure

- Perform the entire procedure two more times with fresh materials. This will show that your results are repeatable.

Graphing Your Results

- Combine the data for each trial.

- Graph the concentration of glucose on the x-axis and the number of Positive Toward Glucose on the y-axis.

- On a separate graph, graph the concentration of glucose on the x-axis and the number of Neutral on the y-axis.

- On a separate graph, graph the concentration of glucose on the x-axis and the number of Negative, Away from Glucose on the y-axis.

Ask an Expert

Global Connections

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) are a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all.

Variations

- Try other chemicals, such as sugars, salts, amino acids, etc.

- Try soaking the strips in cultures of Physarum's "natural" diet, such as bacteria or yeast.

- Try mixing an attractant chemical with a chemical you've found to be a repellent.

- Make a 1-cm-diameter round punch to cut out and transfer Physarum polycephalum cultures.

Careers

If you like this project, you might enjoy exploring these related careers: