Wearable Electronics: Sewing an LED Patch

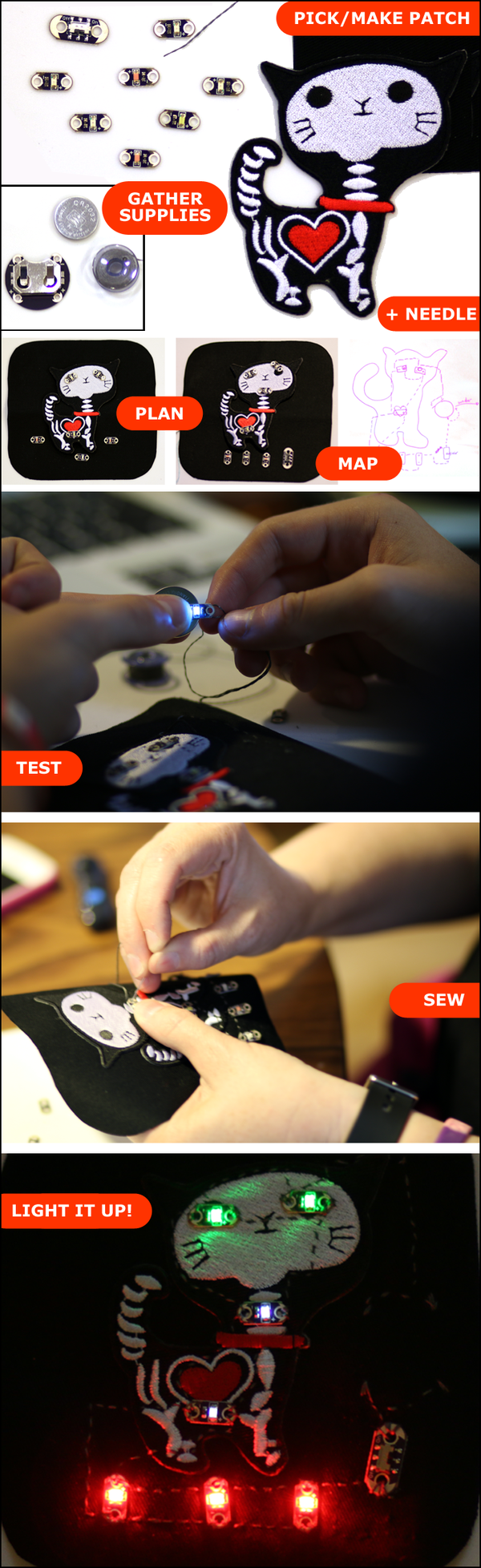

Whether you draw a patch from scratch or pick one up readymade, adding LEDs to a patch really lights things up. With needle, conductive thread, LEDs, and a power source, students can transform accessories or clothes into wearable electronics.

This summer, I pulled up the LED Dance Glove: Get the Party Started with Your Own Interactive Light Show project idea at Science Buddies and decided to give wearable circuits another try. My attempt a few years back hadn't gone exactly as planned. This year, determined to sew some light-up fun, I took a new approach. Despite the fact that using permanent markers on a scrap of canvas and drawing a patch to wire can be a super cool way to explore wearable electronics, this year I browsed online and picked a ready-made patch. (Your patch can be anything, really, and if you order online, you can find thousands of patches from which to choose.) Once I had a patch in hand for my electronics project, I was ready to sew a circuit to add some simple light-up flair!

Planning the Patch

Depending on how you want to use the patch, you may decide to sew your circuit directly to the surface of a bag, or you may need to mount it so that it can be easily removed. (Mounting the patch may also help protect your circuit.)

Note: For a first-time project, or a project with kids, you should consider using only one or two LEDs. This simplifies the circuit and makes it much easier to ensure success.

For my own bag, I didn't want to sew the patch and circuit directly through the interior fabric of my messenger bag, so I decided to mount my skeleton kitty patch onto a larger piece of background canvas. This approach gave me more surface area onto which to sew the circuit and gave the patch a bit more overall stiffness. This also protects the underside of my circuit because it isn't "right there" on the inside of my bag. Instead, it's on the underside of the patch, sitting between the top of the patch and the bag. Concealing the circuitry this way reduces the risk of the circuit getting damaged when I am getting things in and out of the bag.

With my patch mounted on a backing piece (another layer of durable canvas), I plotted out where I wanted to add LEDs and where the on/off switch and the battery holder would go. For a first-time project, or a project with kids, you should consider using only one or two LEDs. This simplifies the circuit and makes it much easier to ensure success. This also reduces the drain on your battery, which means your patch will stay lit longer from a single battery.

My plan involved multiple LEDs, probably too many. But before I did anything else, I decided where I would add light-up accents to work with the patch and give it a bit of fun when flipped on. It is very important to lay out the components before you start so that you can then draw a diagram to use when sewing the circuit.

Draw a Circuit Map

One of the trickiest parts of sewing an e-textile, I think, is visualizing the traces. The "trace" is the path of stitches made with conductive thread that will connect the components to the power supply. Electricity will run along the trace to light the LEDs up. When you sew the components in place, the line of stitches connecting the positive side of each LED needs to move, uninterrupted, from the positive side of the battery pack to each LED. The negative side of each LED then needs to connect in an uninterrupted line of stitches all the way to the negative terminal of the battery pack. The positive and negative traces cannot cross or touch.

This may sound easy enough, but if you are using a number of LEDs, it can quickly become tricky to keep paths from crossing or touching. Before you start, you want to really think through where you are going to sew to make sure that you don't have a plan for your stitches—a plan for each trace. Drawing your circuit out on a piece of paper is a very important step.

Tips for Sewn Circuits Success

This year's patch project turned out great. It went so smoothly this year that I immediately sewed a second one. That one went even better.

With sewn circuits, you can't tell until the end if the circuit will work as you expect. You carefully sew all of the components in place, insert a battery, and flip the switch to turn the flow of power on and light it up. If it doesn't light up, you will need to spend time troubleshooting to figure out where the circuit is failing. Be prepared that troubleshooting your sewn circuits may be necessary.

The following tips and suggestions may help you ensure a fun and successful wearable electronics sewing experience with your students:

- Keep it simple. Start out with one or two LEDs to help simplify the sewn circuit. This minimizes the risk of the trace lines overlapping or touching and lets you really see how the process of sewing a circuit works. Add more LEDs on your next project, but start small!

- Work with a light-colored background. For your first projects, use a light-colored background so that the stitches are easier to see. (Conductive thread is often grey, and it can be very difficult to see on dark fabric.)

- Know your colors. Not all LEDs will show up with the same brightness and intensity. If possible, test your LEDs beforehand so that you understand what each color will look like before you start. (The first time I sewed my patch, I used a few pink LEDs, along with a few red, green, and white ones. When I flipped it on, one of the colors was disappointingly dim compared to the others, so much so that I redid the sewn circuit using other LEDs. I wished I had tested the colors first!)

- Test your parts. Testing your LEDs to make sure they "work" is a good idea. You don't want to get all the way finished and find that the one in the middle is faulty. One way to test an individual LED is to hold the positive end of it to a coin cell battery and then connect the negative end with a scrap of conductive thread to the bottom of the battery. You can do this in your hand, but be careful—it can get hot, and you may see a spark or two.

- Check your trace. If the circuit doesn't work, look carefully at the positive and negative lines of stitches to make sure nothing is touching or crossing that should not be. It can sometimes be hard to spot a problem, especially if you are working on a dark fabric, but if you see lights flickering, not turning on at all, or, worse, turning on even when the switch is flipped to off, you will need to carefully check your circuit diagram and your stitches to make sure things are sewn in place properly.

- Keep your stitches small. Small stitches that are close together will help minimize the risk of problems with the circuit. Similarly, when you begin and end your threads, trim the excess so that there are no floating strands that will touch other threads and create a short circuit.

- Stock plenty of batteries. Depending on the number of LEDs you use, you may find that the battery dies quickly. With a single regular coin cell battery, you won't want to leave your circuit on for long periods of time. Save the power for when you really want to make a statement!

- Know the difference between series and parallel circuits. To maximize your sewn circuit experience, you need to know the difference between series and parallel circuits. You can explore these fundamental electronics principles in the LED Dance Glove: Get the Party Started with Your Own Interactive Light Show project, or in projects like Electric Play Dough Project 2: Rig Your Creations With Lots of Lights! and How to Turn a Potato Into a Battery.

- Take your time. Depending on the complexity of your circuit or number of LEDs, it will take a while to sew things in place. Remember, if using LilyPad LEDs (which I did), it is often recommended to sew through each hole three times. Take time to pull your stitches through firmly and securely and follow your diagram.

- Don't get frustrated. Your circuit may not light up at first, and it can be difficult and time-consuming to remove stitches and resew part of a circuit or start all over. If your circuit doesn't work, first try a fresh battery. If it still doesn't work, carefully check all of your traces to make sure nothing is touching or crossing. Follow the line of stitches from the positive of the battery holder to all of the positive sides of the LEDs. Do the same thing with the negative trace. If you lay the fabric flat and pull it taut, does your circuit work? Does the circuit flicker on and off? Spend time working through what you see happening and rework your stitches, as necessary. Don't give up!

In the end, have fun! You can really let your personality shine with your own wearable electronics. We would love to see what you create!

See also:

Categories:

You Might Also Enjoy These Related Posts:

- Plastics and Earth Day - Science Projects

- Arduino Science Projects and Physical Computing

- 10+ Robotics Projects with the BlueBot Kit

- 5 STEM Activities with Marshmallow Peeps

- March Madness Basketball Science Projects: Sports Science Experiments

- Women in STEM! More than 60 Scientists and Engineers for Women's History Month

- Explore Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning with Student AI Projects

- 10 Reasons to Do the Rubber Band Car Engineering Challenge