Abstract

Have you ever tried an apple that tastes like a banana? It sounds weird, but what actually makes the apple taste like an apple? Our tongue is definitely important for identifying food flavors, but if you have ever had a stuffy nose, you probably noticed that your smell contributes to taste as well. Which of those senses has more influence on flavor? Imagine eating an apple and, at the same time, smelling a really strong banana scent. How to you think the apple will taste? Will the nose or the tongue win the "flavor battle"?Summary

This project requires the participation of volunteers. Make sure you are familiar with your science fair's rules about tests involving human volunteers before you start. For suggestions and common rules check out the Science Buddies resource Projects Involving Human Subjects.

Objective

Investigate the effect of smell on taste and determine which sense (taste or smell) has greater influence on food flavor.Introduction

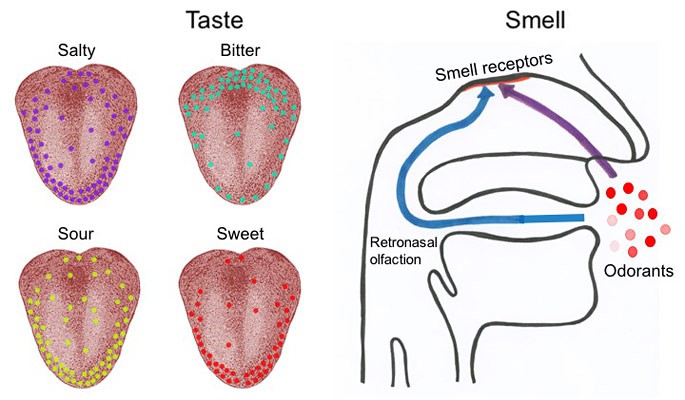

Do you have a favorite food? Can you explain what exactly makes you like this food so much more than others? Is it its yummy taste, its wonderful smell, or perhaps its perfect texture? It might not be so easy to pick just one reason—it is most likely a combination of all of these! There is more to flavor than just taste. In fact, the tongue is not the only part responsible for sensing the unique flavor for every food we eat. The experience of flavor is the combination of taste and smell (figure 1).

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons users Rainer Zenz, LC Uni Hohenheim / Public Domain

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons users Rainer Zenz, LC Uni Hohenheim / Public DomainTwo diagrams showing the taste and smell receptors located on the tongue and inner nose respectively. Four images of the tongue show the location of taste buds for four different tastes: salty, bitter, sour and sweet. The top-left diagram shows the location of salty taste receptors -- grouped closely around the tip and sides of the tongue and sparse around the center and back of the tongue. The bottom-left diagram for sour taste receptors has a similar distribution of receptors to salty taste receptors. The top-right diagram shows bitter taste receptors grouped closely at the back of the tongue and are very sparse at the center, sides and tip of the tongue. The bottom-right diagram shows sweet taste receptors that are densly packed in the tip and sides of the tongue (with a few receptors scattered across the surface of the tongue). The smell diagram shows how odorants enter the body through the nose and mouth and travel upwards to the top of the nasal cavity where the smell receptors are located.

Figure 1. Tasting with your tongue and smelling with your nose. (Image credits: tongue images by Rainer Zenz, via Wikimedia Commons; olfaction image (modified) by LC Uni Hohenheim, via Wikimedia Commons).

When you put food in your mouth, your tongue picks up the five basic tastes: sweetness, saltiness, sourness, bitterness, and umami, which is a savory taste (think of meat or mushrooms). If you look at your tongue closely, you might see tiny bumps on its surface. These are called papillae and each of them harbors many taste buds. On average, each person's tongue has about 2,000–8,000 taste buds, and each of them contains about 50–100 taste receptors. Each receptor is best at sensing a single sensation and sends signals to the brain, which then identifies sweet, salty, bitter, sour, or umami. The total sum of these sensations is the "taste" of the food.

So what about smell? The five basic tastes listed above only partially contribute to the perception of flavor in your mouth. For the rest of the flavor, the scent of the food and your personal sense of smell—also called olfaction—play important roles. Once you put food into your mouth, odorants, which are specific chemicals that are responsible for its smell, enter your nostrils. Inside your nose there are millions of smell receptors. Once the receptor binds to a specific odorant, it sends a signal to your brain and you are able to identify the specific scent. But did you know that your nostrils are not the only way smells can get into your nose? Your mouth and your nasal cavity are connected in your throat! You might have seen a great demonstration of this connection if you have ever seen someone shoot water out of their nose while laughing after they have taken a drink! Smelling through the "back door" of your nose—also known as retronasal olfaction—also contributes to flavor perception when you are eating as you can see in figure 1.

So how does all the information about smell and taste come together? There is a specific part of the brain that is able to pick up and respond to signals from both smell receptors and taste receptors. This area of the brain, called the orbitofrontal cortex, is where researchers think that the information about smell and taste converge to produce the flavor we perceive. This link between smell and taste is so strong that people learn to associate certain smells with a specific taste. For instance, do you feel a sour taste on your tongue when you smell a strong lemon scent? The food industry already makes use of this by introducing phantom aromas into food. By adding barely detectable amounts of odorants into foods, our brain can perceive flavors without realizing that they are not actually there. Some research even claims that the smell of a food accounts for up to 80 percent of how we perceive flavor, compared to 20 percent for taste.

Considering this linkage between smell and taste, it should be easy to change a food's flavor by just changing its smell. So, do you think you can make an apple taste like a banana? Well, head into the kitchen, gather some food, scents, and volunteers, and find out!

Terms and Concepts

- Flavor

- Taste

- Smell

- Five basic tastes

- Papillae

- Taste bud

- Taste receptor

- Olfaction

- Odorant

- Smell receptor

- Retronasal olfaction

- Orbitofrontal cortex

- Phantom aroma

Questions

- Why do different foods taste different?

- What are the five basic tastes and how can we detect them?

- Which sense is most important for flavor detection?

- How are the sense of smell and the sense of taste connected?

- What other factors, besides taste and smell, influence our perception of food and its flavor?

- How can we influence or manipulate flavor and where do you think this knowledge could be useful?

Bibliography

- KidsHealth. (n.d.). Your nose. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- KidsHealth. (n.d.). What are taste buds?. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- Scientific American. (2008). How does the way food looks or its smell influence taste?. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- The Atlantic. (2015). Tasting flavor that doesn't exist. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

For help creating graphs, try this website:

- National Center for Education Statistics, (n.d.). Create a Graph. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

Materials and Equipment

- Molecule-R Aroma E-evolution kit, available from Amazon

- Spoons (2 per food sample and volunteer plus one extra spoon per volunteer)

- Mini plastic cups with lids, 2 oz (1 for each food and 2 for each scent), available from Amazon

- Medicine dropper

- Cotton balls without perfume (2 for each scent), available from Amazon

- Blindfold (scarf, eye mask, or swim goggles covered with paper)

- 10 different foods, see Table 1 in the Procedure for more details (1 jar each)

- Glass of water (1 per volunteer)

- Volunteers (8 or more) (Note: To find out how many volunteer subjects you need, check out the Science Buddies resource Sample Size: How Many Survey Participants Do I Need?)

- Cardboard box

- Permanent marker

- Pens or pencils

- Lab notebook

Disclaimer: Science Buddies participates in affiliate programs with Home Science Tools, Amazon.com, Carolina Biological, and Jameco Electronics. Proceeds from the affiliate programs help support Science Buddies, a 501(c)(3) public charity, and keep our resources free for everyone. Our top priority is student learning. If you have any comments (positive or negative) related to purchases you've made for science projects from recommendations on our site, please let us know. Write to us at scibuddy@sciencebuddies.org.

Experimental Procedure

Working with Human Test Subjects

There are special considerations when designing an experiment involving human subjects. Fairs affiliated with Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) often require an Informed Consent Form (permission sheet) for every participant who is questioned. Consult the rules and regulations of the science fair that you are entering, prior to performing experiments or surveys. Please refer to the Science Buddies documents Projects Involving Human Subjects and Scientific Review Committee for additional important requirements. If you are working with minors, you must get advance permission from the children's parents or guardians (and teachers if you are performing the test while they are in school) to make sure that it is all right for the children to participate in the science fair project. Here are suggested guidelines for obtaining permission for working with minors:

- Write a clear description of your science fair project, what you are studying, and what you hope to learn. Include how the child will be tested. Include a paragraph where you get a parent's or guardian's and/or teacher's signature.

- Print out as many copies as you need for each child you will be surveying.

- Pass out the permission sheet to the children or to the teachers of the children to give to the parents. You must have permission for all the children in order to be able to use them as test subjects.

Preparing Your Food and Scent Samples

You can prepare most of your samples the day before doing the taste test and keep them in the refrigerator overnight, if necessary. Keep in mind that some foods lose their flavors when stored for too long, so some samples may have to be prepared the day of the test. Table 1 lists some choices for food/scent pairs that you can try for your experiment. The food/scent pairs were chosen to include a selection of uncommon food/scent pairs (in which the food and the scent are not similar and do not match, such as squash/coffee or mustard/chocolate) and common food/scent pairs (in which the food and the scent are similar and match, such as strawberry/banana or applesauce/cinnamon).

| Food | Scent |

|---|---|

| Uncommon Food/Scent Pairs | |

| Peas (baby jar) | Mint |

| Squash (baby jar) | Coffee |

| Cream cheese | Vanilla |

| Carrot (baby jar) | Strawberry |

| Ketchup | Cinnamon |

| Mustard | Chocolate |

| Peanut butter | Vanilla |

| Banana (baby jar or yogurt) | Coffee |

| Hummus (plain) | Banana |

| Common Food/Scent Pairs | |

| Sweet potato (baby jar) | Cinnamon |

| Strawberry (yogurt) | Banana |

| Banana (baby jar or yogurt) | Strawberry |

| Plain applesauce (baby jar or regular applesauce) | Cinnamon |

| Nutella/Chocolate pudding | Mint |

| Carrot | Butter |

| Plain applesauce (baby jar or regular applesauce) | Vanilla |

| Peanut butter | Coconut |

| Vanilla (yogurt) | Banana |

It is important that all the food that you choose for the experiment has a very similar texture and temperature, as both of these parameters can affect flavor as well. The easiest way to get similar-textured food is to buy a variety of already prepared, mashed-up food, such as baby food. Table 1 is based on foods that you can already buy prepared. Some of them come in small baby food jars, others in the form of yogurt. Follow the step by step instructions below to prepare your samples for the taste test and click through the slideshow to see the sample preparation procedure.

- Choose 10 food/scent pairs from table 1 that you want to try for your experiment (a mix of common and uncommon pairs).

- Label one mini cup for each food with a consecutive number and with a clean spoon fill each mini cup with one of the foods that you selected.

- In your lab notebook, write down which number corresponds to each food.

- Stir each food well so they all have a similar texture. If you perform your taste experiment the same day, keep the food outside of the refrigerator so it is at room temperature.

- Number an empty mini cup for each scent.

- For each scent get two cotton balls and put one drop of scent solution on each. They should not be too wet, but the smell should be noticeable.

- Put the cotton balls into a labeled mini cup and close the lid so the smell stays inside. Write down which number corresponds to this scent.

- Repeat steps 6–8 with all the other scents you chose. Make sure you rinse your medical dropper in between scents.

- Take one extra set of two cotton balls and put one drop of tap water on each of them. Remember to rinse your medicine dropper really well! These cotton balls will be your control smell samples, which you will use to test the taste of food without an extra smell.

- Put all your prepared food and smell samples in a cardboard box so the volunteers will not be able to see them during the taste test.

Performing the Taste Test

Ideally, your surroundings should be free of strong and distracting smells while performing the taste experiment. Your volunteers should also be free of colds so they can actually taste the food and smell the scents during the experiment. Be sure all samples are at room temperature when you have your volunteers taste them, since temperature can affect flavors. Try out the taste test yourself first so you know the procedure and can explain it to your volunteers better. Do not include your data in the data sheet.

- Recruit your volunteers for the taste test (8 or more). Let them know the day and time of your experiment and how long it should take (approximately 15–30 minutes). Be sure to ask them if they have any food allergies so you do not include those foods in your samples.

- Write a single list with all the available flavors in your experiment (including all foods and scents, for example: Apple, cinnamon, banana, mint, squash, coffee...). Order all the flavors alphabetically to avoid grouping the scents and foods together. Hand this list to your volunteers before starting the taste test but do not tell them which one is a food and which one is a scent.

- Prepare one data table, like table 2, in which to write down all the responses from each volunteer during the taste test.

- In your data table, fill in the list of all of your food/scent samples, as shown in table 2, with each food sample first listed with the extra scent and then without (control). Instead of "Food 1" and "Scent 1," write down the actual food/scent pair for this sample number. To do the control tests, pick the food you want to test and use the control cotton balls (with only water on them) during the taste test.

- When doing the taste test, pick a random sample number sequence from table 2 to use for each volunteer in order to vary between different food samples, as well as control samples and samples that contain extra scents. This way the volunteers cannot make out any patterns and do not know if the cotton ball contains a scent or not.

| Sample # | Food Sample | Scent Sample | Volunteer Number | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ... | |||

| 1 | Food 1 | Scent 1 | |||||||||||

| 2 | Food 1 | Control | |||||||||||

| 3 | Food 2 | Scent 2 | |||||||||||

| 4 | Food 2 | Control | |||||||||||

| 5 | ... | ... | |||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||

| ... | |||||||||||||

| 20 | |||||||||||||

- Do the taste test with one volunteer in the room at a time so that the other volunteers do not hear any responses before it is their turn to try the food/scent samples.

- Assign each volunteer an identification number so that your data can be recorded anonymously.

- Explain to your volunteer that you are doing an experiment to find out how smell influences flavors of different foods. Tell them that you will give them a variety of food samples to taste in combination with different scents to smell, chosen from the list of flavors on the sheet you gave them. Also tell them that they will need to be blindfolded during the test so that they will not be influenced by what the samples look like. Remind them that all the food samples consist of regular foods and that none of them are disgusting.

- Before you start the taste test, blindfold your volunteer and only then get your food and scent samples out of the box. Have a glass of water ready for your volunteer.

- Before actually starting the taste test with food and scent samples, tell your volunteer you will do a test run first, as explained in step 11 but with an empty spoon and with plain cotton balls. The testing procedure can be confusing at first, as the volunteer needs to eat and smell at the same time, so a test run will help it go more smoothly for both of you. Repeat the testing procedure without food and scents until the volunteer feels comfortable with the procedure and can manage to eat and inhale at the same time.

- Perform the taste test starting with your first volunteer. Use a fresh spoon for each food and each volunteer:

- Pick the first food/scent pair from your list and take the corresponding food and smell samples out of your box.

- Take a little sample of the food with a fresh spoon and ask the volunteer what hand he/she would prefer to hold the spoon with. Then put the spoon into the preferred hand of your volunteer as shown in figure 2. Tell him/her to NOT eat the food yet.

Image Credit: Svenja Lohner, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Svenja Lohner, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 2. Passing the food sample to your blindfolded volunteer.

- Take the two cotton balls with the scent out of the mini cup and explain to the volunteer that you will hold two cotton balls in front of his/her nose that might or might not contain a specific smell. Keep the cotton balls in your hand for now.

- Before the tasting starts, tell your volunteer that he/she should exhale deeply to make sure his/her lungs are completely empty. He/she should hold his/her breath and NOT inhale again until you tell them to.

- Now hold the two cotton balls (with or without the smell) very close to the volunteer's nose (one in front of each nostril) so that they touch their nose a little bit. You can use both hands or only one hand to do this as shown in figure 3.

Image Credit: Svenja Lohner, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Svenja Lohner, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 3. Performing the taste test with food and smell samples. Notice how the cotton balls are placed very close to the volunteers nose during testing.

- Once the cotton balls are in place, tell your volunteer that he/she can put the spoon with the food into his/her mouth and start eating while slowly inhaling at the same time (figure 3).

- As soon as they start eating and inhaling, ask the volunteer what flavor comes first into his/her mind. Let them choose one flavor from the list you gave them. You might need to read it out to them once more so they can pick one of the flavors. Note: It is very important that the cotton balls stay close to the volunteer's nose until he/she has swallowed the food and has told you what flavor he/she identified.

- Write down the volunteer's response in your data table (for example: Pea, banana, carrot etc.).

- Before you test the next food/scent pair, tell your volunteer to drink a sip of water as shown in figure 4 to cleanse their taste buds before trying the next food.

Image Credit: Svenja Lohner, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Svenja Lohner, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 4. Drinking a sip of water helps cleansing the taste buds in between samples.

- Repeat step 11 for the next food/scent pair until you have tested each of the foods you chose, both with and without an extra scent on the cotton ball. Use fresh spoons every time that you give your volunteer a food sample.

- Once one volunteer finishes all your samples, thank your volunteer and start the same experiment with your next volunteer. Remember to use fresh spoons and a fresh glass of water.

Analyzing Your Data

- Once all your volunteers have completed the taste test, take your data table with all their responses. Circle the responses that accurately match the food's real identity (correct responses). Did the volunteers' responses match the real food identity more often in test samples or in control samples?

- Count the total number of correct responses for food samples with extra scents and the total number of correct responses in your control samples without extra scent.

- Make a bar graph from your results that reads "food with smell sample" and "food with no smell sample" on the x-axis and shows the number of correct responses for each on the y-axis. Do you see any differences in the total number of correct responses between test samples and control samples?

- What does your result tell you about the influence of smells on the taste of food?

- To find out which sense (taste or smell) is more important for food flavor, look at your data table and compare the volunteers' responses for the same food in test samples (with extra smell) and control samples. Do this for each food that you had in your experiment.

- For all your test samples, separately count the number of responses that matched the food sample ("taste match"), and the smell sample ("smell match"). If a response did not match either of them, count them as "no match." Do the same for all the control samples. Note that in this case you will only have "match" and "no match" responses.

- Make a bar graph and on the x-axis show "food with smell sample - taste match," "food with smell sample - smell match," "food with smell sample - no match," "food with no smell sample - match," and "food with no smell sample - no match." On the y-axis, plot the corresponding number of responses that you have counted. Is one category much larger than the other?

- Looking at the results on your graph, can you answer the question about which sense wins the food flavor battle? Why do you think this is the case and how could that knowledge help enhance the flavor of foods?

- What other information can you deduct from your data? Can you find one scent that dominated all the tastes? Or was there one food taste that dominated all the scents? Are sweet smells more prominent than or more subtle than other smells?

Ask an Expert

Variations

- Table 1 showed you a list of recommended food/scent pairs for your taste experiment in this project. Try to create new combinations with different foods and another variety of smells (you can even make your own, such as garlic oil or lemon scent). Consider common food and scent pairings (in which the smell complements the chosen food), as well as uncommon food scent pairs in which the smell does not fit the chosen food. Which combination will be more confusing for your senses?

- Can you think of other factors, besides smell and taste, that influence the flavor of foods? What if you present your volunteers with the same food but with different textures (unchanged, chopped, blended, dried, etcetera)? Will they notice a difference in flavor? What about temperature? Does it matter if food is frozen, at room temperature, or heated? Design an experiment similar to this one to find out.

- Do you want to find out if phantom aromas really work? Research has shown that, for example, ham or beef odors make people think that their food is saltier. On the other hand, vanilla flavor is very strongly associated with sweetness and fools people into believing that there is more sugar in their food than there actually is. Create your own "phantom aroma food" and try it out yourself.

- How will your food taste if your only way of "smelling" is through retronasal olfaction, or "smelling" through your mouth? Another way to test the influence of smell on food flavor is described in the Science Buddies' project The Nose Knows Smell but How About Taste?

- Do you want to find out if you are a Supertaster? Some people have many more taste buds than the average person, and therefore have the ability to perceive flavors much stronger and more intensely than others. Find out how many taste buds you have in this project from Science Buddies: Do You Love the Taste of Food? Find Out if You Are a Supertaster!

Careers

If you like this project, you might enjoy exploring these related careers: