Abstract

Have you ever heard of the NASA Mars rovers Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance? How about the "bomb squad" robots that police and the military use? These are places that are hard for us to reach (Mars), or dangerous for us to be near (explosives). Because the human operators are usually far away from the robot, driving one is different from driving a car. Operators rely on information sent back from the robot, including pictures and video. In this project, you will build your own simple mobile robot and test your ability to operate the robot when you cannot see it.Summary

Ben Finio, Ph.D., Science Buddies

- PackBot and Roomba are registered trademarks of the iRobot Corporation.

Objective

Build a simple robot using a radio-controlled toy car and a wireless video camera. Test your ability to drive the car when you can only see the video from the camera compared to when you can actually see the car.Introduction

Humans use robots for many different things. Some robots in factories automatically put things together. Some robots look like, and even talk like and interact with, humans (the kind of robot you will see most often in movies). Some do things that humans find boring, like vacuuming. Others do things that are dangerous or difficult for humans — this means no human lives are put at risk.

The NASA Mars rovers are a great example of robots that do something difficult - going to Mars! Figure 1 below shows a computer image of the Mars Science Laboratory rover nicknamed "Curiosity."

Image Credit: NASA / Public domain

Image Credit: NASA / Public domain

Figure 1. A computer image shows the Mars Science Laboratory (nicknamed "Curiosity"), by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and NASA.

One day, scientists hope to send humans to Mars, but until we figure out how to do that safely, it is easier to send robots (for example, the trip to Mars is very long, so humans would have to pack lots of food — but robots do not need to eat). Because it takes a long time for radio signals to get from Earth to Mars (can you find out how long?), the rovers have to be partially autonomous. Autonomous means that a robot can decide on its own where to go and what to do, without direct instructions from a human. A fully autonomous robot really has a mind of its own and does not take any instructions from humans. Most robots today are partially autonomous — they can make some decisions on their own, but still take directions from their human operators. For example, NASA team members set broad goals and destinations for the Mars rovers, but they cannot give detailed instructions on how to drive around every single rock or over every bump on the Martian surface. The rovers have sensors to help them observe their environment and decide how to do things like move around rocks. Sensors are devices that let a robot gather information about its environment, just as humans use sight, hearing, touch, and taste. For example, you use your eyes to see the world around you, and a robot uses a camera. You use your ears to hear sound, and a robot uses a microphone. Robots use many other types of sensors — for example, they can use lasers to figure out exactly how far away an object is, without touching it!

An example of a robot that does something dangerous is a bomb disposal robot. Bomb disposal robots are used by the police and military to safely disarm bombs that may have been planted by terrorists or criminals. The PackBot®, shown in Figure 2, is one example of a bomb disposal robot. (The company that makes it is iRobot®, the same company that makes the Roomba®, a robotic vacuum cleaner.)

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Figure 2. The PackBot is equipped with a camera and radio-controlled robotic arm, which lets soldiers and police officers safely disarm bombs (Wikimedia Commons user Outisnn, 2011).

This helps keep the police and soldiers safe while they do their jobs. Because these robots are used on Earth and not Mars, humans can send wireless signals (or radio waves) to the robot quickly, so the robots are radio controlled. This means a human operator usually drives the robots (a safe distance away from the bomb) using a video game-like controller and watching a video feed from a camera on the robot. This lets the operators "see" from the robot's point of view, even when they cannot actually see the robot (for example, if it is around a corner or on the other side of a building). These robots also went to other dangerous situations — for example, emergency workers used them after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan (see the Bibliography).

If you have ever played with a radio-controlled toy car, you might know how difficult it is to drive the car around a crowded house without crashing into things. Would it be harder if you could not see the car, but only the view from a camera attached to the car? This is what robot operators have to do. In this project, you will make your own search-and-rescue robot with an attached camera and test your ability to drive it.

Terms and Concepts

- Robot

- Mars rovers

- Autonomous

- Fully autonomous

- Partially autonomous

- Sensor

- Bomb disposal robot

- Radio controlled

- Average

Questions

- What kinds of robots are there? Can you find examples of different robots?

- How long does it take a radio signal from Earth to reach Mars? Do you understand why the Mars rovers have to be partially autonomous?

- What types of sensors do humans have?

- What types of sensors do robots have? Can you find examples of robot sensors that humans do not have?

- What types of bomb disposal robots are there other than the PackBot®?

- What can search-and-rescue robots do besides bomb disposal?

- How did emergency workers use robots after the Fukushima nuclear disaster?

Bibliography

- NASA. (2013, May 10). Spirit and Opportunity, Mars exploration rovers. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- NASA and Jet Propulsion Laboratory. (n.d.). Mars Science Laboratory, Curiosity rover. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- Endeavor Robotics (n.d.). PackBot. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- Koren, M. (n.d). 3 Robots that Braved Fukushima. Popular Mechanics. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

For help creating graphs, try this website:

- National Center for Education Statistics, (n.d.). Create a Graph. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

Materials and Equipment

- Radio-controlled (RC) toy car of your choice. Many options are available at toy stores or online.

- Battery-powered wireless camera or a smartphone with a video chat app (Facetime, Zoom, etc.).

- Another device (phone, tablet, or computer) to watch the video from the camera or phone mounted on the car.

- Tape

- Stopwatch

- Multiple rooms in an indoor area for a robot "course" (outdoor area may also be an option, depending on the off-road abilities of your RC car)

- Volunteer to operate stopwatch and keep track of the number of crashes

- Batteries as required by RC car and camera (check packaging/directions)

Disclaimer: Science Buddies participates in affiliate programs with Home Science Tools, Amazon.com, Carolina Biological, and Jameco Electronics. Proceeds from the affiliate programs help support Science Buddies, a 501(c)(3) public charity, and keep our resources free for everyone. Our top priority is student learning. If you have any comments (positive or negative) related to purchases you've made for science projects from recommendations on our site, please let us know. Write to us at scibuddy@sciencebuddies.org.

Experimental Procedure

- Use tape to attach your wireless camera or phone to your RC car. By combining a sensor with a mobile car, you have now made a simple robot. Our robot is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Our search-and-rescue robot, made from a toy RC car and a wireless video camera.

- Set up a video call with the phone or access video from the camera from another device. Ask an adult volunteer to help you with this step if necessary.

- Practice driving the car around your house while walking behind the car and looking at it. Also practice driving it by looking only the video from the camera or phone, but not directly at the car. Once you are comfortable driving the car both ways, move to the next step.

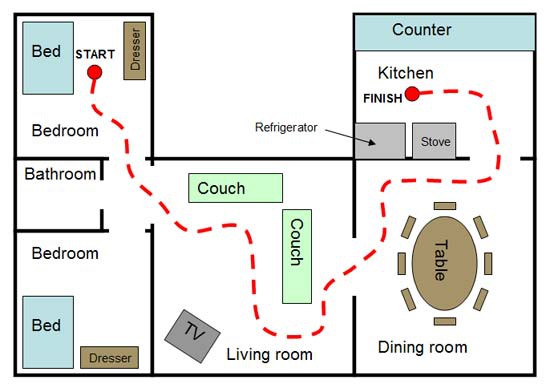

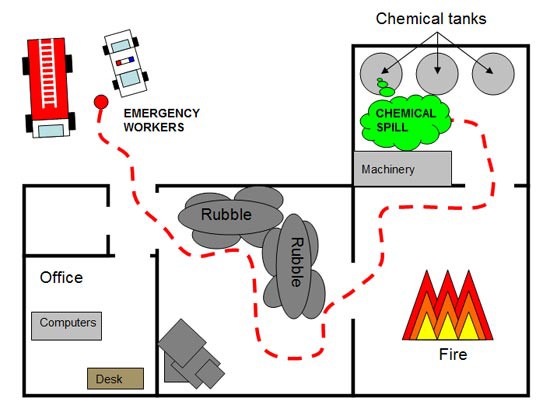

- Plan a route through your house to use as a test course. Sketch a map of your house (include obstacles like furniture), and plot out the route on this map. This is exactly what scientists, engineers, or robot operators would do. For example, NASA uses satellite images of Mars to plan routes for the Mars rovers. (To see for yourself, search Google for "Mars rover route.") Police or military officials may use a map of a city or floor plan of a building to plan routes for their robots.

You can imagine that the map of your house is actually the site of a real-life disaster scenario. For example, you could pretend that you are navigating your robot through a collapsed building after an earthquake to look for survivors; or you could plant a "suspicious package" in your house (which may be a bomb) that your robot needs to investigate; or you could pretend that there has been a chemical spill and your robot needs to take environmental readings to see if the air is safe for humans to breathe. In any of these situations, using a robot to explore helps make things safer for human emergency and rescue workers.

Figure 4 shows an example map of a house, and an imagined scenario where the robot must reach a chemical spill in a factory after an earthquake.

Image Credit: Ben Finio, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Ben Finio, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Ben Finio, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Ben Finio, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Figure 4. An example map showing a planned route through a house (top), and an imaginary disaster scenario based on the layout of the house (bottom).

- Try driving the route while you are walking behind the car, so you can see it the entire time (remember that in a real-life disaster scenario, this would not be safe to do!). Ask a volunteer to use a stopwatch to time how long it takes you to drive from start to finish. Also have the volunteer keep track of how many times you crash the car into something. After you finish, write the numbers down in your lab notebook. It might help to make a table like Table 1 to keep track of your data. (Because you will drive the route more than once, both following the car and watching it only on the TV or monitor, you need to number each trial for both — for example, 1a and 1b, 2a and 2b, and so on.)

| Trial | Watched | Time to Finish (seconds) | # of Crashes |

| 1a | Car | ||

| 1b | TV | ||

| 2a | Car | ||

| 2b | TV | ||

| 3a | Car | ||

| 3b | TV |

- Now try driving the route while looking only at the video from the phone or camera. Do not look at the car! This might be easiest if you are in a separate room that is not part of your planned route. Again, ask a volunteer to time the trip from start to finish and keep track of the number of times you crash the car into something.

- Repeat the experiment at least two more times, so you should have six trials total — three while following the car, and three while only watching the video feed. If you have time, you can do more trials. Add rows to your data table if needed.

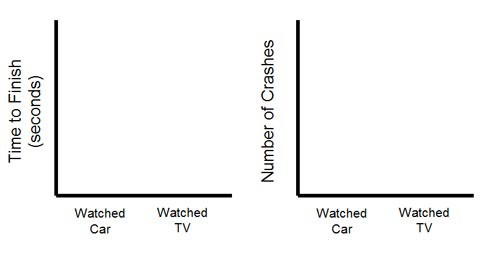

- Make a graph of your results to compare the trials where you followed the car and the trials where you watched only the TV. Make one graph for the time it took you to complete the course and one graph for the number of crashes you had. Plot the individual point from each trial on your graph. You can also calculate an average for all the trials and plot that point on the graph (be sure that the average point looks different from the individual data points). Figure 5 shows examples of how to set up these graphs.

Image Credit: Ben Finio, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Ben Finio, Science Buddies / Science BuddiesTwo example graphs have no data but measure the time to finish and number of crashes of an RC car driving through a course in a house. The RC car is driven through the house under two circumstances, the first is while keeping an eye on the car while it completes the course, and the second is while only watching a screen that shows video feed from the car. Each graph has columns to record data from both scenarios.

Figure 5. Example of how to label the axis for your graphs. The graph on the left is used to compare the time to complete the course and the graph on the right compares the number of crashes while watching the car or watching only the video.

- Using the graphs you made in Step 8, compare your results for driving while watching the car and driving while watching only the video. Which method was faster? Which method had fewer crashes? Which one did you think was easier to do?

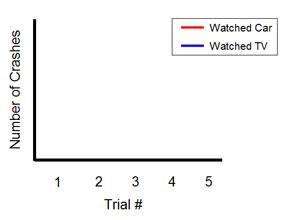

- It would also be interesting to see if you got better at driving the car over time, as you got more practice and did more trials. You can do this by plotting the time it took you to finish or the number of crashes for the trial number for each type of test. Figure 6 shows a blank example graph.

Image Credit: Ben Finio, Science Buddies / Science Buddies

Image Credit: Ben Finio, Science Buddies / Science BuddiesExample graph has no data but measures the number of crashes for an RC car driving through a house. This graph measures the number of crashes on the y-axis versus the trial number on the x-axis, and has two colored lines to represent trials done while watching the RC car and trials done while watching a screen with a video feed from the car.

Figure 6. An example of how to label the axis on a line plot graph comparing the number of crashes for each trial. This graph will whether or not you got better at driving the car the more you drove. You could make a similar graph for the time it took you to complete the course.

- Examine the graphs you made in Step 10. Did you get better at driving the car the more you drove it? Did the time to complete the course and the number of crashes go down? Did they stay about the same, or change greatly from trial to trial? How do you think this affects your results?

Ask an Expert

Global Connections

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) are a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all.

Variations

- Ask other people to volunteer as drivers, and re-run the experiment for each new driver. Is there a performance difference between drivers? Are some people faster than others, or better at not crashing? Are some people better at driving while watching the car, while others are better at watching the TV?

- Some more expensive wireless video camera kits come with multiple cameras. If you purchased one of these kits, can you attach more than one camera to your car? If so, does this make it easier to drive? For example, you could use a "back-up" camera to see where you are going when driving in reverse.

- Does changing where the camera is attached to the car affect your ability to drive it without crashing? For example, how different is driving when you attach the camera to the front bumper, the roof, or the rear of the vehicle?

Careers

If you like this project, you might enjoy exploring these related careers: