What is Big Data?

You might have read or heard the phrase big data used on the internet or in a television commercial. But what is big data? How is it defined, and how is it different from "regular" data? Can you use it for a science project? This reference page will help answer some of these questions and get you started exploring the world of big data.

Data is information, and there are many different types of information. If you have done a science project before, you probably collected information by writing down numbers in a data table, like a distance that you measured with a ruler, or a weight you measured with a scale. You might have used that data to make a chart or a graph, but data does not just mean numbers; it can also be words like names and addresses, or computer files like pictures and videos. For example, your school might store a list of names, ages, addresses, and an identification photo for each student. That list contains several different types of data. Can you think of other types of data that you might use in a science project or in everyday life?

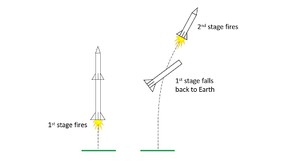

In the past, most data was recorded, stored, and analyzed by hand. The invention and widespread use of computers in the 20th century, followed by the internet, dramatically changed the way we collect and store data. Computers allow us to store data electronically, and the internet allows us to rapidly transfer data from one place to another. Look at Table 1 and Figure 1, below, for some examples of how computers and the internet have changed our ability to collect, store, and analyze data.

| Before Computers and the Internet | After Computers and the Internet |

|---|---|

| Scientists (or students doing science projects!) would record data using a pencil and paper, and draw graphs by hand. | Students and scientists can use spreadsheet programs like Microsoft® Excel® to record large amounts of data and automatically make graphs. |

| People had to rely on huge phone books (with hundreds, or even thousands, of pages) to look up names, phone numbers, and addresses. Phone books do still exist; despite being so large, each one only contains information for one city. | You can use the internet to quickly look up an address anywhere in the world with a service like Google Maps. A single smartphone can store contact information for hundreds or thousands of people, so you can reach them without needing a phone book. |

| To keep track of your purchases, you would have to keep paper copies of receipts for everything you bought. | You can make purchases with a credit or debit card. While you still have the option to get a paper receipt, these purchases are also recorded electronically, and you can log in to your bank account online to view a history of all the purchases you have made. |

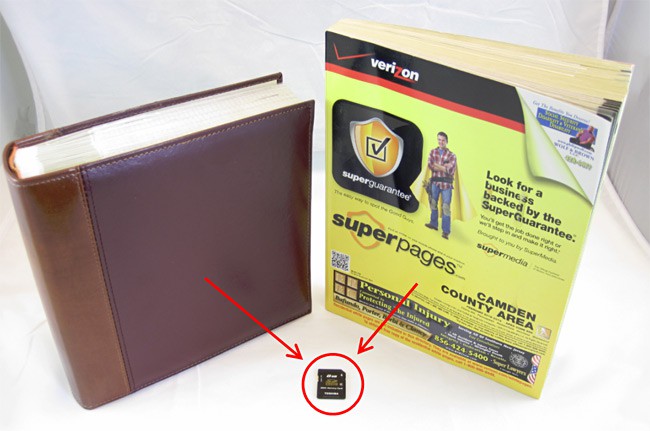

| A large photo album could hold a couple hundred printouts of 4×6 pictures. To share a picture with someone, you would have to get an additional copy printed and mail it to them. | The memory card for a smartphone or digital camera can hold thousands of images. You can instantaneously share them with many people at once using text messages, email, or social media. |

| To look up directions from one place to another, you would have to use a paper map and write down the directions. | You can use a smartphone or GPS device to automatically find directions from one place to another. |

Figure 1. Computers allow us to take entire sets of data that used to be stored separately—like in photo albums and phone books—and store all of that information on one tiny memory card.

However, just because the data is collected and stored electronically does not mean it is "big." Big data refers to the dramatic increase in our ability to collect, store, and process data, thanks to huge increases in computing power. Computing power can include the availability of storage space (like on hard drives, flash drives, and memory cards), the speed of computer processors, and the speed of internet connections, all of which have increased at an incredible rate through the beginning of the 21st century (see the Technical Note, below, for more details). This increase in computing power goes along with a huge increase in the number of devices that are connected to the internet, ranging from smartphones and computers to weather stations and traffic monitors. As a result, we are collecting more types of data more quickly than ever before. This leads to the "three V's" that are used to define big data: volume, velocity, and variety. A "big data" problem can have one or more of the following characteristics:

- Volume refers to the "size" of the data, and it might be the first thing you think of when you hear the word "big." The size of an electronic file is measured in bytes. It might take an average person years to fill up a typical computer hard drive (a few hundred gigabytes) with pictures, songs, video games, and other files. A large internet corporation, on the other hand, could collect terabytes (one terabyte is 1,000 gigabytes) of information every day, which brings us to the next "V," velocity.

- Velocity refers to how quickly the data is generated. Big data does not have to come in the form of large individual files. What if you get a whole lot of small pieces of data, very, very fast? Twitter is a perfect example. Individual tweets are very small (140 characters or less), but there are a lot of them. An individual person might only send a few dozen tweets a day, at most, but overall there are 500 million tweets every day.

- Variety refers to how the type and source of data can vary. Some data might be nicely formatted and have very little variety; for example, a column of numbers in a spreadsheet, like air temperatures recorded over a long period of time. However, other data can be "messy;" a Facebook post could contain text, links, pictures, or videos, and all Facebook posts are different. This can make it harder to extract useful information from the posts (for example, what topics are currently being discussed the most), compared to a simple calculation like calculating the average temperature over a period of several weeks.

While these concepts can be used to help define big data, there is no strict definition of "big." What a small company with a few employees considers big might not be considered big by a large internet company with thousands of employees. Furthermore, what is generally considered big today might not be considered big 5 years from now, as computing power continues to increase. So, big data is a moving target, but as more and more devices are connected to the internet and we continue to collect more and more data, it will continue to be a challenge to deal with that data and do something useful with it instead of letting it go to waste. It will be up to future generations of data scientists, computer programmers, and statisticians to help us analyze big data.

To help you think more about big data, here are some examples of things you might experience in everyday life, and how they can become "big data" problems when viewed on a much bigger scale. Can you identify how the situations described below have a big volume, velocity, and/or variety of data? Remember that any specific "big data" situation must have one or more of the "three V's", but does not have to have all three.

- Think about how many people ride your school bus, and how many trips a day the bus makes. How hard do you think it was for the school to figure out the right bus routes so all students would be picked up? Now, think about how many people ride the entire public transportation system every day in a city near you. In a large city, there can be millions of people who take public transportation every day, on hundreds of different bus and subway lines. The city government can use that information to help figure out the best bus schedules and routes. Some buses might be overcrowded or always running late, and others might be nearly empty at certain times. Analyzing rider data can help the government allocate buses to best meet demand. For some amazing visualizations of commuters riding the subway system in Boston, Massachusetts, see http://mbtaviz.github.io/.

- How many text messages or emails do you send per day? Try to look up how many total messages are sent through a cell phone carrier like Verizon or AT&T, or through a mail provider like Gmail or Yahoo. How do companies handle and use that information when they have millions of customers? Cell phone companies must figure out where to put cell towers so their network can properly handle the load of many users sending messages all at once. Some companies actually analyze the content of messages themselves. For example, Google uses the words contained in emails to decide which advertisements to display on your personal Gmail page.

- Between sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, how many social media posts do you make per day? A couple? A few dozen? Now, think about how many total users those sites have; there are over one billion people using Facebook alone. Facebook analyzes data from its users' posts to determine what information might be most interesting to its users, which can determine what shows up in your News Feed. There are about 6,000 tweets sent every second; Twitter analyzes them all in real-time to determine which topics are currently trending. For a map of tweets sent from all over the world, see https://blog.twitter.com/2013/the-geography-of-tweets.

- How often do you buy something from an online vendor like Amazon.com, rent a movie from Netflix, or buy a song on iTunes? Have you ever seen a "Recommended" section on one of those services, that makes recommendations of additional products, movies, or songs you might like? How do these companies know what you will like? These companies collect data from all of their users' transactions and use them to make recommendations. For example, if lots of people who have a similar purchasing history to you buy a video game and give it a 5-star rating, Amazon might recommend that video game to you.

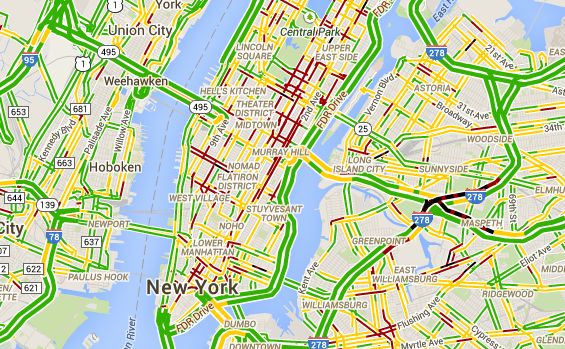

- Try writing down the home addresses of a few of your friends, and writing down directions from your house to theirs. Now imagine taking pictures of the road along the way. How often would you have to update the directions or the pictures based on new construction? What about accounting for traffic to find a faster route? That could quickly become a pretty big job, even for just a few of your friends. Now imagine doing that for the entire world. That is exactly what services like Google Maps do. They allow you to automatically look up directions between two addresses, accounting for real-time conditions like traffic, accidents, and road closures (see Figure 2, below). Google also has to constantly update the database as new roads are constructed and as they take new satellite-view and street-view images.

- What is the weather like as you are reading this? It might be pretty quick for you to look out the window or go outside and determine whether it is sunny or cloudy, about how warm it is, and whether or not it is raining. You can probably remember what the weather was like in your home town yesterday or last week, and you can go online and look up what the weather will probably be like tomorrow. Now, imagine doing that for every city in the country. Organizations like the National Weather Service use data collected from a huge variety of sources (like thermometers, barometers, rain gauges, radar towers, and satellite images) all across the country to record weather data. Not only do they use that information to predict what the weather will be like tomorrow or next week, but they use it to analyze Earth's climate on a global scale. Analyzing data collected since the 1800s has helped scientists determine that human activity has a significant impact on climate change.

A overhead view of New York focuses on Mahattan island with each street highlighted in green, yellow or red. These colors indicate vehicle traffic on that particular street: green for light traffic, yellow for moderate traffic and red for heavy traffic. The map from Google shows that most visible freeways are clear of traffic while many side streets and avenues are heavily congested. Streets to the east of Central park have the highest concentration of high traffic roads.

Figure 2. This screenshot from Google Maps shows traffic data in New York City (green indicates light traffic, darker colors indicate heavy traffic). How do you think Google manages to record and display traffic information for that many roads all at once, and update it constantly? This is definitely a "big data" problem!

Do you now have a better grasp on what big data means? Are you ready to try and tackle big data for your own science project? If you need help getting started, here is a list of existing Science Buddies projects that utilize big data.

Computing power can refer generally to several things, such as:

- The availability of storage space, measured in gigabytes, terabytes, or even petabytes (if you are not familiar with metric prefixes, see this Wikipedia page for reference).

- Increased speed of computer processors, measured in gigahertz (GHz), or operations per second.

- Internet connection speeds, measured in megabytes per second (Mbps) or even gigabytes per second (Gbps).

- Note: If you want to learn more about these topics, research what a typical hard drive size, processor speed, and internet connection speed were like in the 1990s compared to today. You might be amazed by the results!