Explore the “POP” in popcorn

Summary

Introduction

Do you like popcorn? It’s not only a tasty snack but also fascinating to watch when it pops in the pot. But why does it do that? What makes the small popcorn kernel jump into the air and change its appearance? Where does the characteristic popping sound come from and does every corn pop? There are many good questions about such a simple snack. Are you curious to find out some answers? In this activity you will do some popcorn science and even get to snack on your experiment.

Background

There are many corn varieties which can differ significantly from popcorn. Popcorn kernels are not just dried kernels of the sweet corn we eat. Popcorn is a special variety of corn, and it is the only one that pops. The key to popcorn is the unique design of its kernels. Most importantly, its kernel consists of a very hard, mostly non-porous outer shell, called pericarp. Inside the kernel there is not only the seed for a new corn plant, but also water and soft starch granules that serve as a food source during germ sprouting. Although popcorn has been around for thousands of years, scientists only recently resolved the mystery behind the popping sound and the detailed mechanisms of how the popcorn bursts.

The reason why popcorn pops is the trapped water inside its kernel. If the kernel is heated, this water will transform into steam. Due to the hard and mostly non-porous shell, the steam has nowhere to go, resulting in a buildup of pressure inside the kernel. Once the pressure gets high enough and the temperature reaches about 180ºC (360 ºF), the kernel hull bursts and the popcorn is turned inside out. The characteristic popcorn consistency and white-yellowish foamy appearance results from the starch inside the popcorn kernel. With high temperatures, the starch gelatinizes and then expands with the rapid burst of the kernel. Once it cools down, the solidified flake is formed that we know as popcorn. The characteristic popping sound does not originate from the cracking of the hull as originally thought, but results from the vapor release after the kernel has cracked.

There are many different methods of preparing the perfect popcorn including making different popcorn shapes, but all efforts fail if the kernels do not meet the ideal popcorn requirements. The ideal popcorn kernel has an optimal moisture content of about 14% and is popped at a temperature of about 180ºC (360ºF). A common way to assess popcorn quality is its ‘popping yield’, which you can calculate by counting how many kernels pop versus how many remain unpopped when the kernels are heated. You can also evaluate popcorn quality by measuring kernel expansion, which means how big the popped popcorn flakes get. Check out the quality of your popcorn kernels in this activity and get ready to make some popping noise!

Materials

- Adult helper

- Stove

- Pot with lid

- Vegetable oil

- Heat resistant bowl or plate

- Oven mitts

- Teaspoon

- Popcorn (at least 70 kernels)

- Sharp knife

- Three small cylindrical glasses such as champagne glasses

- Optional: scale that can measure 0.1 g increments, water

Preparation

- Prepare three piles of popcorn with 20 kernels each.

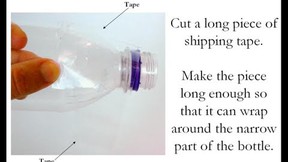

- Ask an adult helper to crack open the hull of all 20 kernels from one pile with a sharp knife. This is best done by making a deep cut into the softer white part at the tip of the kernel. The kernel should be kept whole (not split into pieces), but the hull should be cracked.

- Set your oven to 350ºF. Place one pile of 20 popcorn kernels into a heat resistant bowl and put the kernels in the oven for about 30 minutes. Use the oven mitts when you take them out. Let them cool down to room temperature afterwards. How do the kernels look when they come out of the oven? Did the appearance of the kernels change?

- Keep the last pile of kernels as they are.

- With the help of an adult put the pot on the stove and add 2 teaspoons of vegetable oil into the pot.

- Turn on the stove and set it to high. Make sure you never work on the stove without adult supervision.

- Put 3 extra popcorn kernels (not from your 3 piles) into the pot, close the lid and wait until they pop. You can swirl the pot a little in between so the kernels don’t get burned.

Instructions

- Once the three kernels have popped, remove them with a spoon and turn the heat down to medium. Add the pile of 20 regular, untreated, popcorn kernels into the pot, and swirl it slightly to cover all the kernels with oil. Tilt the lid on the pot so steam can escape but be careful not to let hot oil splash out of the pot.

- Wait a maximum of 2 minutes until all the kernels have popped or the popping has stopped. After 2 minutes take the pot from the stove and remove all 20 kernels. Put them aside for now- don’t eat them yet! How many of the kernels have popped? What size do the flakes have, are they big or small? What color do they have, are they dark, brown or yellow? Was the popping sound very loud?

- Take the pot from the stove and replenish the vegetable oil if necessary. Again, add 3 regular popcorn kernels (not from your pile) and wait until they all pop. Remove them from the pot before you proceed.

- Now, take the pile of popcorn kernels, that you cut with a knife and add them to the pot. Swirl the pot slightly and keep it on medium heat with the lid tilted on top.

- Leave the pot on the stove for 2 minutes, swirling slightly in between, and observe what happens. Take the pot from the stove after 2 minutes and asses your popping results. Did all the popcorn kernels pop? How does the popped popcorn look compared to the previous batch of popcorn? Do you notice any differences? How big are the flakes this time?

- Repeat step 3, 4 and 5 but this time use the 20 popcorn kernels that you had previously heated in the oven. How do they look after 2 minutes of popping? Are there any unpopped kernels? Do you notice any size or color differences compared to the other popcorn? If there are differences why do you think this is the case?

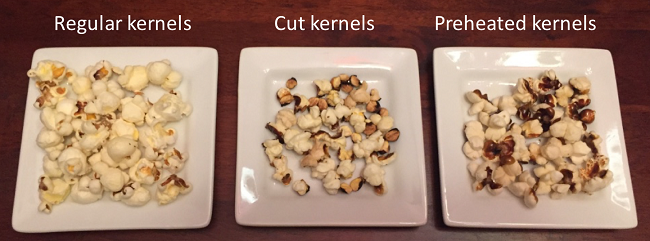

- Take the three small cylindrical glasses and fill each one with a different batch of your 20 popped popcorn kernels (regular, cut and preheated). They should each contain the same amount of popped kernels. Place them next to each other so you can assess the different volumes of the popcorn flakes. Are all the glasses filled up to the same height? Which popcorn kernels expanded the most, which were the smallest? Can you explain the differences?

- Finally, you can sample the popcorn from each of your piles. Which popcorn tastes the best? Is one more chewy or crisp than the other?

Extra: Test to find the ideal popcorn popping temperature. Set your oven to 180-190ºC (360-375ºF) and put a heat resistant bowl with 20 regular popcorn kernels inside. Swirl the bowl occasionally and wait long enough so that the popcorn starts popping. When the popping slowed down and stops, take the bowl out of the oven using the mitts and count the popped kernels. Did all of the kernels pop? Repeat the same experiment but this time set the oven to about 170ºC (330ºF). Wait exactly as long as it took to pop the kernels at 180-190ºC, then take the popcorn out of the oven. How many kernels popped at the lower temperature? What can you infer from your results about the optimal popcorn popping temperature?

Extra: In addition to preheating the popcorn kernels, take another 20 popcorn kernels and soak them in water for a few hours, and dry them off afterwards. Because the kernels will take up some water during the soaking you will increase the percentage of water inside the kernel. Repeat the popping process with these kernels. Will they pop at all? How many of them pop compared to the other popcorn kernels? Are their flakes the same size or bigger/smaller?

Extra: Ideal popcorn kernels contain about 14% of water. You can estimate how much water is in your popcorn kernels by weighing the popcorn kernels (plus oil and pot) before popping and afterwards. From the difference in weight you can calculate the amount of water that has been lost as steam during the popping process. Does it come close to 14%? How could your measurement be improved?

Observations and Results

Did you get some nice fluffy popcorn? With the regular popcorn that you popped you should have gotten some big fluffy flakes from all of the kernels. Once they reach the right temperature in the pot and the vapor pressure inside the kernels gets high enough they burst open and jump into the air producing a nice popcorn puff. It probably didn’t even take 2 minutes for all of them to pop. However, if you popped the kernels that you previously cut and cracked open, the result should have been different. After 2 minutes you might still have had some unpopped kernels, and the ones that did pop didn’t get that big. The cracked kernels produce much smaller flakes because when you damage the outer hull of the kernels, the water vapor that is created during heating can easily escape through the crack that you created in the hull. Therefore, less pressure is built up inside the kernel, which makes it either not pop at all or reduces the flake size after popping.

With the last popcorn batch that you preheated in the oven you should have seen a similar outcome. The kernels probably changed color and turned from yellow to brown during heating in the oven. The flake size should have also been smaller compared to the regular popcorn kernels. As the hull of the kernel is not 100% water proof, preheating the kernels for 30 minutes at low temperature causes some of the water inside the kernel to evaporate. It did not create enough vapor pressure to burst the hull, but instead escaped the kernel through tiny pores in the kernel hull. Because of this reduced water content, the pressure couldn’t build up as high in the preheated kernels, compared to the regular kernels during the popping process, which ultimately leads to smaller kernels. If the water percentage in the kernel is too low, the kernels won’t pop at all because there is not enough pressure buildup.

You should have easily seen the difference in popcorn size and volume once you put the kernels into the glasses at the end of the experiment. Although you put in the exact same number of popped kernels, the glass with the regular popcorn should have been filled up much higher than the other ones, again, demonstrating that these “ideal” kernels pop and expand much better.

Ask an Expert

Cleanup

- Clean up all your dishes. Make sure to let the oil in the pot cool down before you add any water to it. You can eat all of your popped popcorn.

Additional Resources

- Physicists reveal the secrets of perfect popcorn, from The Washington Post

- Popcorn, from How Products are Made

- The Science of Popcorn, from Carolina

- Popcorn Physics 101: How a Kernel Pops, from the Scientific American

- Science Activity for All Ages!, from Science Buddies