Abstract

We tend to think of plants as immobile, but the tendrils of a vine, such as the morning glory, actually move in response to touch. Tendrils wrap around structures, which give the plant something to grow on. In this science fair project, you will investigate how plant tendrils respond to touch stimuli.Summary

David Whyte, PhD, Science Buddies

Objective

The objective of this plant biology science fair project is to investigate the response of a plant's tendrils to touch.

Introduction

A plant's survival depends on its ability to respond to environmental cues. One such response is the directional growth of a plant or part of a plant in response to an external stimulus, called tropism. Plant stems grow up in response to gravity (gravitropism), plant surfaces turn to face the Sun (phototropism), roots grow toward water sources (hydrotropism), and plant tendrils respond to physical touch (thigmotropism). In this plant biology science fair project, you will study thigmotropism in the morning glory tendril.

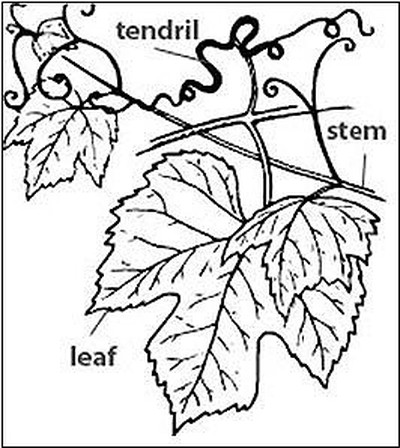

Because of their fast growth, twining habit, and the fact that they are attractive flowers, morning glories and sweet peas are popular vines found in many gardens. The term morning glory is a common name for over 1,000 species of flowering plants in the family Convolvulaceae. Varieties found in many nurseries include sunspots, heavenly blue, and moonflower. There are also many varieties of sweet peas available at most nurseries. Vines, such as the morning glory, grow well on trellises due to their tendrils, which curl around support structures. See Figure 1 for a picture showing a plant tendril.

Image Credit: Wikimedia / Open

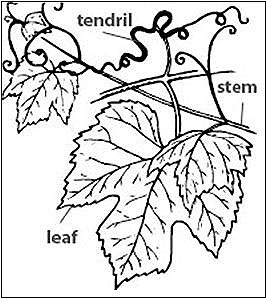

Image Credit: Wikimedia / Open

Figure 1. Parts of a plant, including the stem, leaf, and tendril. Tendrils curl around solid objects to provide support for the plant. (Wikimedia, 2008 [labels added by David Whyte, Science Buddies].)

Consider what needs to happen for a tendril to curl around an object. The surface of the tendril must somehow sense that it has come into contact with an object. Then the tendril must bend in such a way that it curls around the object. One way to make the tendril curl in this direction would be for the side of the tendril away from the object to grow longer. Or the side of the tendril that is touching the object could shrink.

In this science fair project, you will grow morning glory plants and study how their tendrils respond to touch. Specifically, you will determine how the curling of plant tendrils depends on the frequency (times per day) of touch stimuli.

Terms and Concepts

- Tropism

- Gravitropism

- Phototropism

- Hydrotropism

- Tendril

- Thigmotropism

- Morning glory

- Sweet pea

- Convolvulaceae

- Negative control

- Nutation

Questions

- What is the origin for the prefix thigmo-?

- Based on your research, how does the morning glory plant use nutation to find a solid support?

- True or false? Some plants have a more sensitive sense of touch than humans do.

- The curling process has two phases: a quick response that occurs within a few minutes after touching, and a long-term response that determines how the tendril grows into its final shape. Based on your research, what is happening inside the tendril in these two phases?

Bibliography

- Vartanian, S. (1997). Thigmotropism in Tendrils. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- Weiss, R. (2006, September 4). Leave It to Vines to Find Their Own Spines. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- University of California, Davis. (n.d.). Tendrils. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- The Clematis. (2003). A Place in the Sun. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- Vecchione, G. Blue Ribbon Science Fair Projects. Touchy Feely Morning Glories. New York: Sterling Publishing, 2005.

Materials and Equipment

- Seeds for morning glory plants; available at a nursery or garden supply store

- Small pots (8)

- Potting soil (1 bag)

- Permanent marker

- Masking tape

- Pencils for smaller plants or 12-inch wooden dowels for larger plants (16, 2 per pot)

- Stopwatch

- Lab notebook

- Graph paper

- Optional: camera

Experimental Procedure

- This procedure calls for growing vines from seeds, but if you have access to a vine with tendrils that is already growing, that will work just fine.

- This procedure calls for planting two seeds in eight pots of soil, but you should plant more seeds in more pots if you plan to perform the experiments in the Variations section, below.

Growing the Plants

- Label the pots 1 to 8 with the masking tape and permanent marker.

- Plant two morning glory seeds in each of eight small pots. First put about 3 inches of potting soil into the pot. Form a hole and place the seeds in the hole. Then cover them with about 1–2 more inches of potting soil.

- Water the seeds regularly and keep the pots in a warm area, out of the direct sunlight.

- Record the date, the time, the common and scientific names of the plants, the name of the company that produced the seeds, and any other facts or observations that would allow someone to reproduce your experiments in your lab notebook.

- It will take up to three weeks for the plants to grow and form tendrils.

Observing Tendril Response to a Solid Support

- When the plants have each produced several tendrils, insert a pencil into the soil near one of the tendrils.

- Place the pencil in the pot so that it is touching the tendril.

- Arrange the tendril and support so that the middle of the tendril is in direct contact with the support.

- If needed, gently secure the stem of the plant to the pencil with a little piece of tape so that the tendrils are in contact with the pencil.

- Repeat step 1 for two more tendrils.

- Observe the tendrils for the next 24 hours, as each first touches the pencil, and then as it curls around the pencil.

- Keep a record of your observations, including times, in your lab notebook.

- If desired, take pictures of the vines to add them to your lab notebook for your display board. You can also make drawings.

- Make a graph of time vs. the degree of curling. For example, graph the following times:

- First sign of curling

- Curled at 90 degrees

- One full rotation

- Two full rotations, etc.

Experimenting with Stimuli

Now that you have healthy plants with tendrils, experiment with the stimuli that result in the tendrils starting to curl. Specifically, investigate how the frequency of physical contact affects curling. To stimulate curling in the tendrils, you will first mark a region on 12 tendrils with a permanent marker. You will then touch them at different times, with a pencil, and record their response to touch. Take careful notes of when you touch each tendril.

- Mark one spot on 12 tendrils with a permanent marker, as follows.

- Choose tendrils from various plants.

- Mark each tendril in approximately the same region; for example, near the middle of the tendril.

- The mark should be about 1 cm long.

- Keep track of each of the 12 tendrils. You might want to take a picture of the plants each day and label the tendrils on the picture. You could also make drawings. You could also use different colored markers to help keep track of the tendrils.

- Pick three tendrils that will not be marked with the permanent marker. These tendrils will be the negative controls. These tendrils should not touch the pencil or any other solid object.

- The negative controls will be numbered on your picture or drawing as 13, 14, and 15.

- Touch (always with the pencil and always timing with the stopwatch) tendrils 1–12 at different times of the day, as follows:

- Tendrils 1, 2, and 3: One time per day for 30 seconds in the morning.

- Tendrils 4, 5, and 6: Three times per day, for 30 seconds each time, in the morning, afternoon, and at night.

- Tendrils 7, 8, and 9: Six times per day for 30 seconds. Six times over the course of the day.

- Tendrils 10, 11, 12: These tendrils should be in constant contact with a support, such as a pencil, as they were in the previous section.

- Tendrils 13, 14, and 15: These tendrils receive no stimulus.

- Record the time it takes for the tendrils to start curling.

- Check several times a day, with the first time being as soon as you wake up in the morning, and the last time being just before you go to bed for the night.

- Record the degree of curl—such as 90 degrees, one full rotation, two full rotations, etc.—in your lab notebook.

- Graph the time it took for each tendril to start curling vs. the number of times it was touched.

- Graph the time it took for each tendril to make one full rotation vs. the number of times it was touched.

Ask an Expert

Global Connections

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) are a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all.

Variations

- Change the frequency or duration of the touch stimuli.

- Try touching other parts of the tendril, such as the tip.

- Use another plant type, such as a sweet pea.

- Can you make a tendril uncurl if you touch the outer surface of the curled tendril?

- Try hanging threads of different thicknesses on a tendril to gauge its sensitivity to touch.

- For an advanced variation, use a microscope to investigate how the cellular structures of the tendrils change in response to touch. Cut off one full turn of the tendril, including the tip. Cut off a thin slice from the outside edge of the tendril and a thin slice from the inner edge of the tendril. Put each slice on a clean cover slip and investigate each slice under a microscope. Relate the structure of the plant tissue, as observed under the microscope, to the curvature of the tendril.

- Is it possible that plant tendrils have ways of finding surfaces to climb on? For example, a plant's tendrils might respond to shade produced by a wall, or to chemicals produced by branches. Try to prove or disprove this claim experimentally.

- Produce a stop-action film of a tendril "finding" a support and then curling around it.

Careers

If you like this project, you might enjoy exploring these related careers: